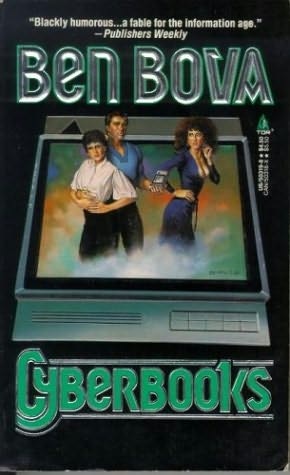

Found via Nate’s Ebook News: Ben Bova, author of the Cyberbooks e-book satire novel (which recently became available as an e-book itself), has an editorial in a local Florida newspaper about the current e-book situation. Given that he was one of the first recent SF writers to consider the idea of e-books seriously, it is interesting to see what he has to say.

Found via Nate’s Ebook News: Ben Bova, author of the Cyberbooks e-book satire novel (which recently became available as an e-book itself), has an editorial in a local Florida newspaper about the current e-book situation. Given that he was one of the first recent SF writers to consider the idea of e-books seriously, it is interesting to see what he has to say.

Bova writes that his premise in Cyberbooks was that “electrons are cheaper than paper.”

Ninety percent of a book publisher’s expenses are the cost of hauling paper across the countryside: from paper mill to printing plant, from printing plant to book distributors’ warehouses, from warehouses to book stores.

I figured that a book published electronically could go directly from the publisher’s office to the retail buyer, via the Internet. Publishers could save enormous expenses.

He goes on to talk about how e-books are now with us, but that just like in his satire, things are starting to go “drastically wrong.” Apart from people feeling uncomfortable reading on a screen (to which Bova. a long-time e-book enthusiast even apart from Cyberbooks, has a classic retort), he brings up the Amazon/Macmillan price feud:

Amazon wanted to price the books it offers on Kindle so low that they could corner the market on electronic books. Macmillan countered that they couldn’t make a profit on books sold at such low prices.

He then gets the order of events wrong when he says that it was Apple’s introduction of the new iPad that got Amazon and Macmillan to come to an agreement. In fact, it was the introduction of the iPad, and Apple’s agency pricing model, that kicked off the dispute to begin with when Macmillan decided they liked the idea and wanted Amazon to use it too.

Finally, Bova wonders whether, since the production costs are so much lower for e-books, authors should get a bigger share of the royalties than in the past. (In fact, Macmillan’s John Sargent has said that Macmillan will be looking at increasing the e-book royalty percentage to authors under the agency model.)

Amazon vs. Macmillan Redux

It’s interesting to consider the ways that “TeleReading” has changed things even in the lifetime of one author. And not even just the e-book aspect. Back when Bova wrote Cyberbooks in 1989, he probably could not have imagined that one day an editorial he wrote for a local paper might be read and discussed by people all over the world.

It’s funny that the Bova, whose work predicted the modern e-book market in a number of ways, still has a few misconceptions about the e-book industry. For starters, does he not see any irony in the fact that he starts out talking about how e-books should be a lot cheaper because they cost so much less to produce (a fact which many in the publishing industry would and do dispute) and then goes on to complain about Amazon selling e-books too cheaply for publishers to make a profit?

But I have to disagree slightly with Nate the Great’s response, too:

Um, no. Macmillan was making a profit on the ebooks. And I would argue that you are wrong about Amazon’s motive. They’re not trying to corner the market (which is impossible to do on the internet); they’re selling ebooks at the price that people want to pay.

I’d remind him that Macmillan was making a profit on them only because Amazon was selling a lot of them at a loss. They weren’t going to go on doing that forever, “price people want to pay” or not. And if they couldn’t “corner” the market, they could at least grab up a Microsoftian chunk of it.

Sooner or later, the publishers feared, Amazon might present them with an ultimatum: lower their wholesale prices to where Amazon could sell at a profit, or stop selling e-books. Of course, that’s all academic now.

Printing Costs vs. E-book Price

And publishers will tell you that e-books actually don’t cost that much less to produce, and that printing costs certainly aren’t “ninety percent” of them. If the publishers are to be believed, the printing costs for a hardcover are pegged at only a couple of dollars per unit, which leaves over $20 of price unaffected.

Hardcovers cost so much not necessarily because of printing costs, but because they’re the publishers’ first crack at getting a large chunk of the other production costs (editing, typesetting, advance, etc.) paid off—and because they are targeted at the crazy people who want to own their favorite author’s new book right away and damn the financial cost.

It is true that Baen sells its e-books at $6 each, but Baen’s execs seem to view e-books as a promotional side-project and apparently do not assign them a proportional tranche of the manuscript’s non-printing-related costs—so Baen can sell them cheaper without fear of cannibalizing its printed book sales.

(And even Baen sells a more expensive and less proofed $15 “E-ARC” version for people who just can’t wait—just like hardcovers are priced higher for people who “just can’t wait” for paperback.)

That’s quite a difference in philosophy from other publishers, and it is uncertain whether Baen will be able to keep it up when e-books are 50% or even 25% of the book market rather than 5% or less as they are now.

It is an interesting time for the e-book industry, and the future is still too hard to predict. But consumers are making it clear that they share Bova’s point of view that e-books should be less expensive, and how the publishers respond to sales figures from their new agency pricing model might make a considerable difference in how quickly the e-book market grows.

Maybe it’s time for a sequel to Cyberbooks.

“…Baen’s execs seem to view e-books as a promotional side-project and apparently do not assign them a proportional tranche of the manuscript’s non-printing-related costs”

Not saying you’re wrong or anything, but… do you have a link for this info? And how would you calculate a ‘proportionate tranche’? By sales numbers? By dollars sold? By profit percentage? How do other publishers split the costs of producing a book between electronic and paper versions?

I’ve been wondering for a while how much money the Webscriptions store is making, and if you have any info it would be appreciated. After all, I’ve been praising Baen pretty much forever for their ebook strategy, and it would be terribly embarrassing if they then went bust because of it.

Having said all that, $6 isn’t too far off the average price I pay for an ebook at Fictionwise, after discounts and rebates…

“…it is uncertain whether Baen will be able to keep it up when e-books are 50% or even 25% of the book market rather than 5% or less as they are now.”

One question it might be worth asking is if Baen’s ebook vs pbook sales share is any different to the industry as a whole; I would have thought that Baen would have attracted more e-readers than average.

The problem I have with the whole “printing costs are only a couple of dollars per unit” argument is that it is true only in the current business model. The current publishing business model is built around printing hardbacks, with the investment in infrastructure and scale necessary to match. The barriers to entry in the business are huge, which is why publishing has coalesced into the “Big Six.” But in a future digital world, hardbacks don’t drive everything, and the entire business model has to change. The infrastructure is less, the barriers to entry drop, and competition can increase. That’s not to say hardbacks go away, just to say their importance will decline, and the current Big Six will have to change their entire business models or slowly die off the way newspapers are dying off.

While I don’t have a dollar figure for Baen’s ebook sales, David Drake’s obit for Jim Baen in 2006 noted:

“While e-publishing has been a costly waste of effort for others, Baen Books quickly began earning more from electronic sales than it did from Canada . By the time of Jim’s death, the figure had risen to ten times that.”

If that helps any…

Bests to all,

–tr

“I’d remind him that Macmillan was making a profit on them only because Amazon was selling a lot of them at a loss. They weren’t going to go on doing that forever, “price people want to pay” or not. And if they couldn’t “corner” the market, they could at least grab up a Microsoftian chunk of it.”

Amazon only sells at a loss on the $9.99 titles that are discounted from the higher $25ish (hardcover equivalent) list price. Not on the $9.99 titles that list for less. A big chunk of Amazon’s $9.99 titles are discounted from $14-$15 with a print equivalent of a Trade PB or with pubs like Macmillan a MMPB. Some pubs have been charging a $14 list on ebooks that are $8 in print and then bitching when Amazon discounts to $9.99

What people are forgetting is that Baen is selling directly to the customer, not through a distributor like Amazon. In fact, if you take the new model Amazon has where the publisher gets 70%, those same books would have to cost $8.50 if sold by them as kindle editions.

Now consider how much an average Baen paperback sells for on Amazon, and then reduce the publisher profit accordingly due printing to distribution costs. Get the picture? As books go digital, Baen is actually set to make more money, not less. They may be cannibalizing some of their hardcover sales, but the numbers there are pretty low to begin with and all it does is shift the earning split between hardcovers and paperbacks so it covers ebooks as well.