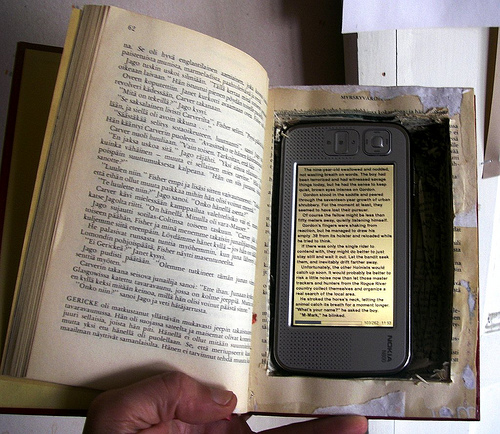

Do we read faster on paper than on the screen? Bob Sutton feels he gets better comprehension out of paper books, and so often buys both paper and electronic copies of volumes he needs to read for research. He was curious enough about this to see if anyone had done studies on the matter.

Do we read faster on paper than on the screen? Bob Sutton feels he gets better comprehension out of paper books, and so often buys both paper and electronic copies of volumes he needs to read for research. He was curious enough about this to see if anyone had done studies on the matter.

While he didn’t find any studies on comprehension, he did find studies that suggested the iPad and Kindle offer reading speeds 6 to 10% slower than printed books—though as he noted further down, other studies suggest the advantage may be going away as displays get better. It would be interesting to see how the retina screen of the new iPad 3 compares.

Meanwhile, on Australian news site The Punch, Chris Harrison laments the decreasing literacy of the current young generation. He discusses a young job applicant whose cover letter ended in a smiley:

[S]he is part of a generation which, more and more, is reading less and less. This is having a negative impact on writing skills, depth of expression and, in this case, employment prospects, at least while her employers belong to Generation X.

Harrison blames, at least in part, e-books, going back to the easy distraction factor of reading books on a gadget that can do a dozen other different things, all of which clamor for readers’ attention. It’s “harder” for people to read books uninterrupted, so they don’t read as much, to his way of thinking—which is why they’re less literate.

He also waxes nostalgic about print e-books—he’s one of those readers who is in love with the kinesthetics of the printed page, which naturally tends to color his way of thinking.

The slow-death of the printed book is the saddest cultural event of my lifetime. I am a bookworm on the brink of extinction. Each time a bookshop closes another hectare of my natural habitat disappears. When I eventually buy a Kindle I will reluctantly appreciate buying books at the touch of a button and certainly won’t miss the freight costs each time we move. But I will miss the physical company of books, the journey through the pages and the crease on the spine.

I just don’t see the appeal. Perhaps it’s because I grew up in the first PC generation, but I’ve never had any trouble reading off the screen. I’m happy to read a printed book, but also happy to read an electronic one.

And I’m not so sure I’d be quick to blame screens for a lack of reading, either. Going back to the job applicant with the smiley, where did she learn to use smileys exactly? In text-based communication on the Internet. And how do you absorb text-based communication? You read it.

It also brings to mind an interesting conversation I had with someone lately. I can’t remember exactly who it was—I want to say it was one of my relatives who came to visit my Mom in the wake of her amputation, and that she works at a school where she would have an opportunity to observe this first-hand, but I’m not positive—but she was saying that cell phone texting is now actually helping kids learn to spell better.

It used to be that SMSing led to people using abbreviations even in the school papers they wrote, but now I’m told that it’s a badge of honor for kids to send messages full of perfectly-spelled full-length words—because the “cool” thing is to have phones with full alphanumeric keypads, and the way you “prove” you have one is by using whole words.

It also brings to mind the book I Live in the Future & Here’s How It Works, which addresses a lot of the same concerns about what computers and Internet media are doing to our minds.

Great post, Chris. This Sutton fellow sounds like he has been reading Danny Bloom’s blog posts over the past 5 years about this very subject, as well as Danny’s contention, er hunch, that reading on paper is superior, brain-chemistry wise, for info processing, info retention and info analysis, not due to convenience or smell of book or ereader design, but due to the way the reading brain reads on paper surfaces vs reading on screens. In fact, as you remember, Danny coined the term “screening” for what we do when we “read” on screens. Great piece. Where can i find mr Sutton?

I also told Bob: You sounds like u has been reading Danny Bloom’s blog posts over the past 5 years about this very subject, as well as Danny’s contention, er hunch, that reading on paper is superior, brain-chemistry wise, for info processing, info retention and info analysis, not due to convenience or smell of book or ereader design, but due to the way the reading brain reads on paper surfaces vs reading on screens. In fact, as you might know, Danny, Tufts 1971, coined the term “screening” for what we do when we “read” on screens. Great piece.

My hunch is that future studies using MRI and PET SCAN machines will show that reading on paper lights up different and superior regions of the brain for three things: info processing in the reading brain, info retention and info analysis. At the moment nobody is doing this research as it is not sexy, and is very expensive and nobody wants to go down this road. But Danny Bloom does and Danny Bloom knows that his hunch will be provem right, not by anecdotal evidence but by hard science, neuroscience. I have 25 PHD professors in my corner now but nobody will go public because they fear for their careers and their images. But watch. I am right about this. I think you know this too, Bob, in your gut. Right?

Great post, Bob. You sounds like u has been reading Danny Bloom’s blog posts over the past 5 years about this very subject, as well as Danny’s contention, er hunch, that reading on paper is superior, brain-chemistry wise, for info processing, info retention and info analysis, not due to convenience or smell of book or ereader design, but due to the way the reading brain reads on paper surfaces vs reading on screens. In fact, as you might know, Danny, Tufts 1971, coined the term “screening” for what we do when we “read” on screens. Great piece.

My hunch is that future studies using MRI and PET SCAN machines will show that reading on paper lights up different and superior regions of the brain for three things: info processing in the reading brain, info retention and info analysis. At the moment nobody is doing this research as it is not sexy, and is very expensive and nobody wants to go down this road. But Danny Bloom does and Danny Bloom knows that his hunch will be provem right, not by anecdotal evidence but by hard science, neuroscience. I have 25 PHD professors in my corner now but nobody will go public because they fear for their careers and their images. But watch. I am right about this. I think you know this too, Bob, in your gut. Right?

I have been reading for sixty years. I’ve been online for twenty of those years and reading ebooks on a PDA or iPod for eight of them. I’m an abnormally fast reader. I detect *no* difference in reading speed or absorption between paper OR computer screen OR PDA/iPod.

I might also add that my writing improved immeasurably thanks to hanging out on Usenet, web fora, and Wikipedia. I write online daily; I don’t want to make a fool of myself with bad spelling or grammar; I hope my posts are readable and interesting.

@Zora, re: ”I detect *no* difference in reading speed or absorption between paper OR computer screen OR PDA/iPod. ”

I take you at your word and believe you. We will not “know” if my hunch is right or wrong until the ”hard science” data comes in, via MRI and PET SCAN research over the next 10-15 years. I might be completely wrong on this, and I am more than willing to admit it too. And your anecdotal evidence is important to listen to, too, and I am listening. Thanks for posting.

In the end, neuroscience will tell us. Studies are going on right now but they won’t be published in academic papers or journals for another 20 years or so. Just rememer I said all this in 2012. Let’s see what the future says about my eccentric hunch!

MRI brain imaging lab studies differences in screen, paper reading

by danny bloom FICTION but read between the lines…it might true in future!

April 20, 2010

BOSTON — Dr Ellen Marker studies reading. But not off screens or in

paper books.

Her research is done in a Quincy laboratory.

The pioneering neuroscientist analyzes brains in their most enthusiastic

reading state, hoping to understand the differences between reading

off screens and reading on paper surfaces.

Like me, Dr Marker feels that her studies will show reading on paper

is superior to reading off screens in terms of

retention, processing, analysis and critical thinking.

But first, let’s see what the scans will be like.

Dr Marker asks me to put myself into an fMRI machine so she and his

team can study which areas of the brain are activated by reading text

on paper compared to reading the same text on a computer screen or a

Kindle e-reader.

And this is why I’m here. Today I will donate my brain scans to science.

Among the things that Market has discovered so far is that reading on

paper might be

something we as a civilization should not ever give up.

“Even though reading on screens is useful and convenient, and I do it

all the time, I feel that

reading on paper is somethine we should never cede to the digital

revolution,” Marker, 43, says. “We need both.”

On the day I climb into the brain imaging cocoon, I am thinking about

what it all might mean.

But since I am just a guinea pig and not a scientist, I will have to

wait for the results.

I enter a sterile lab, and Marker and her four associates greet me,

all in white lab coats.

As they hand me my a pale blue gown to change into, I have

second thoughts — “How can I read while lying down horizontally my

back, not my preferred reading mode?” — but decide to push myself.

Science needs me!

The scientists load me into the machine and I’m off.

Next step: They strap my head down, because any movement distorts the

brain imaging. Ever try to read a book without facial movements?

I feel as if I’m being shoved into the middle of a toilet paper roll,

the walls so close my eyelashes almost graze them.

Then I hear a voice through the earphones I’m wearing. It’s Dr Marker.

“You okay in there?” she asks.

Graduate student Dan Smith, 52, tells me to relax before

running around to join the other scientists in the control room.

With the invention of the fMRI only 20 years ago, along came the

ability to look at brain activity. Marker says that by understanding a

function as gigantic as reading, how the reading brain does its magic

dance, a response that hijacks all of

one’s attention, she might also learn how reading on screens could be

inferior to reading on paper.

“The more we understand how the brain works,” she says, “the more we

will be able to help people modulate its activity.”

As the machine switches on, it sounds like a jackhammer. I follow

Marker’s instructions and as I do, the group watches my brain on

their computer monitors. I willl read passages from a novel, and then

later I will read

the same passages on a Kindle. I just hope the Kindle does not blow up

inside the brain scan machine!

Research and teaching take up most of Marker’s time, but when she has a

spare moment, she thinks about what all this might mean for the future

of humankind.

During my first hour in the fMRI machine, researchers map my brain’s

reading paths

to find out which parts correlate to

which regions of the brain.

“You have 10 minutes,” Marker says through my earphones near the end

of our test. “Keep reading.”

On the

other side of the glass pane, the scientists can see my brain lighting

up as I read on paper and as I read on a screen. Regions light up in

different ways, Marker says.

Komisaruk discusses what her research could do for the future of

humankind. “We need to know

if reading on screens is going to be good if it replaces all our

reading on paper.”

Marker’s lab has paid me a

$100 subject fee, so I want to give them their money’s worth.

After all, it’s not easy to get funding for this stuff — Marker

says she spends at least half of her time applying for grants.

“There’s no premium on studying paper reading modes versus

screen-reading modes in this society,” she tells me

as Smith murmurs, “What do you expect? The gadgetheads want to take over.”

When the tests are over, Market tells me the data takes two hours to

convert, but it can take much longer to

make sense of it.

“We’ll be at this for a while,” she says.

One of the biggest conundrums turns out to be a nagging

question for all mankind: What if reading on screens is not good

for retention of data, emotional connections and critical thinking skills?

Marker begins slipping more and more

into her thoughts. “Neurons, little bags of chemicals, create

awareness,” he says, “but how? How does the brain create the mind?

What is reading, really?”

I see that at the heart of all her research, there is a

philosopher trying not only to understand reading, but also figure out

the nuts and bolts that make up the human experience.

“It’s the hard question I want to answer,” she says. “What creates

consciousness?

“I find that,” she adds, “and I find the Nobel Prize.”

I’m in the same situation as Zora, although she’s been reading for ten years more than I have. 😉

Also, my children all grew up with computers from a very early age, and all three are highly literate. I think you’ll find that literacy levels depend critically upon parent support and teaching, not on screen or paper.

The gap in literacy which we’ve seen generally in the population over the past few decades is due to a theory of learning by osmosis, which became popular in the 60s. Phonics, syllabification and spelling/grammar rules were no longer taught. This theory was incorrect: people do pick up language, but after a certain point, they need to understand how it works.

Fortunately, we have returned to teaching phonics, but have had to re-educate teachers who weren’t taught these basics. If you want to improve your language skills, review phonics, syllables and spelling/grammar rules, and read/write as much as possible. 🙂

I totally disagree with the contention that reading is slowed on eReaders! If you rule out the folks who are so technophobic or non-gadget savvy, focussing on the actual reading, eBooks speed up the reading IMMENSELY!

First, they are easier to hold. Secondly, you can adjust the text size to suit up your preference. Not to mention that the increased portability means you can read at times you might not have been able to when a new release meant a huge hardcover tome.

With all the comments above, re Zora and Clytie and observer x, etc, what this comes down to really, Chris, is anecdotal evidence vs hard science, neuroscience. And we don’t have the hard science yet, and we may never be able to get it. There will always be some people who prefer paper surface reading for their reasons, and there will always be others who prefer screen reading, and those in the middle who see no real difference. So be it. Later the hard science might tell us something. Then again, there might be nothing for science to tell us. Let the MRI and PET scan studies begin!

Guess who said this quote and where it was printed?

–”I received a Kindle for my birthday, and enjoying “light reading,” in addition to the dense science I read for work, I immediately loaded it with mysteries by my favorite authors. But I soon found that I had difficulty recalling the names of characters from chapter to chapter. At first, I attributed the lapses to a scary reality of getting older — but then I discovered that I didn’t have this problem when I read paperbacks.

When I discussed my quirky recall with friends and colleagues, I found out I wasn’t the only one who suffered from “e-book moments.” Online, I discovered that Google’s Larry Page himself had concerns about research showing that on-screen reading is measurably slower than reading on paper.”

”Do E-Books Make It Harder to Remember What You Just Read?” by Maia Szalavitz at TIME:

Digital books are lighter and more convenient to tote around than paper books, but there may be advantages to old technology.

Oh for goodness sakes … this is so much utter bullsh1t. This is nothing more than camouflaged paper fetishism masquerading as pseudo science. Why people get sucked into the argument is a complete mystery to me. It smacks of flame bait trolling to me.

Howard, if you read more slowly on screen above, you would see that said there are three POV on this, paper is better, screens are better, both are good for their own reasons. No one has paper fetishism here. There is no argument here. We are just waiting for hard science to weigh in later. Read the TIME story first and then come back here and comment. Be kind, sir. This is a civilized chat here, no need for BS word. Please!

Mr Bloom. My comments relate to the Teleread article. This article includes three stories. They do not reflect the three viewpoint your patronising comment suggests, and the TIME story (a regurgitation of several article in 2011) is another example of this nonsense.

I stand by my comment about paper fetishists, and I don’t need any pompous advice on my language thank you very much.

Howard, I agree with everything you say. You are a gentleman and a scholar. and it is people like you who give ereader fetishism a bad name! Sigh. Grow up, sir! Who are you, anyways? Do you haev a website where i can see what you really stand for instead of hiding between your first name with no references? I thought you were a good person at first, now I see you are angry unhappy dude. Hope you get better.

Kate Garland, a lecturer in psychology at the University of Leicester

in England, is one of the few scientists who has studied this question

and reviewed the data. She found that when the exact same material is

presented in both media, there is no measurable difference in student

performance.

However, there are some subtle distinctions that favor print, which

may matter in the long run. In one study involving psychology

students, the medium did seem to matter. “We bombarded poor psychology

students with economics that they didn’t know,” she says. Two

differences emerged. First, more repetition was required with computer

reading to impart the same information.

Second, the book readers seemed to digest the material more fully.

Garland explains that when you recall something, you either “know” it

and it just “comes to you” — without necessarily consciously recalling

the context in which you learned it — or you “remember” it by cuing

yourself about that context and then arriving at the answer. “Knowing”

is better because you can recall the important facts faster and

seemingly effortlessly.

“What we found was that people on paper started to ‘know’ the material

more quickly over the passage of time,” says Garland. “It took longer

and [required] more repeated testing to get into that knowing state

[with the computer reading, but] eventually the people who did it on

the computer caught up with the people who [were reading] on paper.”

Fiction or non-fiction, I like to underline important points or good prose to go back and ruminate over, make notes in margins, just demolish a book. That’s a lot more work on a Kindle, for sure.

I don’t know about my comprehension, but I do think I read faster on my Kindle than a printed book.