According to a March 9 story in the Wall Street Journal, The U.S. Department of Justice is considering suing Apple and five large US publishers for allegedly colluding to raise the price of ebooks.

According to a March 9 story in the Wall Street Journal, The U.S. Department of Justice is considering suing Apple and five large US publishers for allegedly colluding to raise the price of ebooks.

At the heart of the issue, I suspect, is concern over the agency pricing model. Agency pricing allows the publisher (or the indie author) to set the retail price of their book.

Although Smashwords is not a party to this potential lawsuit, I felt it was important that the DoJ investigators hear the Smashwords side of the story, because any decisions they make could have significant ramifications for our 40,000 authors and publishers, and for our retailers and customers.

Yesterday I had an hour-long conference call with the DoJ. My goal was to express why I think it’s critically important that the DoJ not take any actions to weaken or dismantle agency pricing for ebooks.

Even before the DoJ investigation, I understood that detractors of the agency model believed that agency would lead to higher prices for consumers.

Ever since we adopted the agency model, however, I had faith that in a free market ecosystem where the supply of product (ebooks) exceeds the demand, that suppliers (authors and publishers) would use price as a competitive tool, and this would naturally lead to lower prices.

I preparation for the DoJ call, I decided to dig up the data to prove whether my pie-in-the-sky supply-and-demand hunch was correct or incorrect. I asked Henry on our engineering team to sift through our log files to reconstruct as much pricing data as possible regarding our books at the Apple iBookstore.

We shared hard data with the DoJ yesterday that we’ve never shared with anyone. I’ll share this data with you now.

As background, Smashwords is one of several authorized aggregators supplying ebooks to the Apple iBookstore. On day one of the iPad’s launch, we had about 2,200 books in the iBookstore,  and our catalog there has grown steadily ever since.

and our catalog there has grown steadily ever since.

Henry was able to assemble a complete data set going back to October 2010. We created once-a-month snapshots of the Smashwords catalog at the Apple iBookstore between October 2010 and March 2012. Our data captures the average price of our titles in the iBookstore, and the number of titles listed.

I’m sharing four data sets. The first data set, above at left, shows the number of Smashwords titles for sale in the Apple iBookstore. As you can see, the numbers have grown steadily. I’m not aware of any other agency pricing study that worked against such a large body of data.

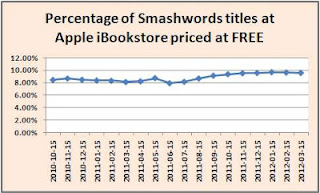

In the next data set, we plotted the percentage of books priced at FREE by our authors and publishers. As you can see from the chart, the number grew from 8.45% in October 2010 to 9.60% this month.

In the next data set, we plotted the percentage of books priced at FREE by our authors and publishers. As you can see from the chart, the number grew from 8.45% in October 2010 to 9.60% this month.

Why would authors and publishers give away complete books when they have the power to price at a price? The reason is because FREE is a powerful marketing tool for platform building, and for introducing new readers to an author’s backlist.

This data indicates a slow but steady increase in the adoption of FREE.

For you statistics geeks out there, the data represents a statistically significant trend with a tau of 0.516 and a 2-sided pvalue of .00313. For you non-stat-geeks, a positive tau number indicates an upward sloping trend, and the pvalue represents the statistical odds that the trend is invalid. A 2-sided pvalue of .00313 indicates that the odds of this trend not being statistically significant is only 3 in 1,000.

In the next chart, I aggregate all books, both FREE books and priced books, to calculate the average price of the books in the catalog.

In the next chart, I aggregate all books, both FREE books and priced books, to calculate the average price of the books in the catalog.

The downward sloping trend is pronounced. The tau is -.948, indicating a downward trend, and the 2-sided pvalue is .000000049141. So, if I’m counting my zeros correctly, that’s less than a 1 in 100 million chance that this trend is not statistically significant.

Dizzy yet?

In plain English, we’ve seen the average price of books in our catalog drop from $4.16 in October 2010 to $2.97 today.

In the next data set, we removed the free titles to identify the true average price for priced books in our catalog at Apple.

In the next data set, we removed the free titles to identify the true average price for priced books in our catalog at Apple.

This statistically significant data set carries a tau of -0.908 and a 2-sided pvalue of 0.00000017217. This confirms that even if you remove FREE books, the average price of priced books is declining. The tau indicates 1 in one million chance that the indicated trend is incorrect.

In plain English, the average prices have dropped 25% from $4.55 in October 2010 to $3.41 today.

Back in 2009, I blogged at the Huffington Post that the time had come for publishers to price ebooks at $4.00. That day arrived for Smashwords authors and publishers a year ago.

The $3.41 is a really interesting number, for a couple reasons: 1) It shows that authors and publishers, left to their own free will, are pricing their books lower in this highly competitive market. Sure, they could all try to fleece customers by pricing their books at $29.99, but customers won’t let them. 2) $3.41 is remarkably close to the average price paid for Smashwords books purchased at Barnes & Noble during the last 30 days. The B&N number: $3.16. I looked at every Smashwords book sold at Barnes & Noble between February 28 and March 27, then calculated the average price. This means Smashwords authors are pricing their books close to what customers want to pay. The median price (represents the midpoint, where an equal number of books sold at lower prices and and equal number sold at higher prices) was $2.99.

We had a good conversation with the DoJ. They were very interested to learn about our business, and learn about the underlying dynamics of the retail distribution ecosystem from the perspective of indie authors and small publishers.

I explained how when Smashwords first began distributing ebooks to retailers in 2009, our retailer contracts were under the traditional wholesale model. After Apple introduced the agency model in early 2010, we found ourselves managing dual, incompatible pricing systems. Apple priced at agency, and our other retailers continued to discount.

As I explained to the DoJ, Apple was aware that our other retailers were underpricing them, not just because we were juggling wholesale and agency, but because Apple prices in $.99 tiers. As we explained to Apple two years ago and to the DoJ yesterday, if a Smashwords author priced a book at $1.25, we’d bump the price at Apple up to $1.99 rather than price lower than what the author wanted.

The DoJ asked me if Apple ever balked at the knowledge that other retailers were selling our same books for less, and my answer was no. Not once in our two year relationship with Apple have they ever complained about a Smashwords-distributed title priced lower at one of their competitors. They’ve never price-matched any of our books if they found it lower elsewhere. I really don’t think they care.

For our other large retailers – Barnes & Noble, Sony and Kobo – I can think of less than five instances combined where any of them tried to price-match books because they found them priced lower elsewhere.

There’s only one retailer that has made it a practice to strictly enforce most-favored-nation pricing upon its authors and publishers, and they’re the retailer that forced us to move all of our wholesale retailers to the agency model. As I mentioned in my initial blog post here, our move to agency in 2010 was necessitated by Amazon’s automated price matching.

At the time, when Sony or B&N discounted a $2.99 book by a mere 5%, Amazon price-matched the book which dropped the author from a 70% royalty rate at Amazon to 35% (Some time after October 2010, I believe Amazon stopped dropping the royalty rate upon price-matching). At the time, our bestselling authors were understandably upset, because the downgrade was costing some of them thousands of dollars in lost income. It caused some of them to remove their books from all retailers except Amazon out of fear of such punishment. Keep in mind, in mid 2010, Amazon controlled 80-90% of the US ebook market, so such policies put authors in a tough bind.

In mid-2010, with our authors angry over the discounting, and with them removing books from distribution (as a distributor, we care about this on multiple levels!), we started asking our retailers to move us to agency terms so our authors could control their pricing. At first, they all said no. None of them were fans of the agency model at that time. I think all of them felt as if the model had been shoved down their throats by the ultimatums of the Big 5 publishers (who viewed Apple and its agency model as their white knight counterbalance to Amazon).

In November 2010, Kobo moved us to agency, and then the next month Barnes & Noble and Sony gave us agency terms as well. I think they all moved us to agency because they realized that their discounting was causing indie authors to remove their books and sell only on Amazon.

Over the last two years, my appreciation for the agency model has grown as I’ve come to fully understand its benefits for our authors, publishers, retailers and customers. Here’s why I support agency:

- Agency puts the authors and publishers in control over their retail price and their promotions. This gives authors and publishers the freedom to coordinate promotions across all retailers for reasons decided by the author or publisher.

- Publishers earn 60-70% of the retail list price as their earnings, vs. 35-50% under the traditional wholesale pricing model. This gives authors and publishers the freedom (should they choose to exercise it) to price their books lower, yet still earn the same or more income from the sale of each unit. This allows our authors to compete more effectively against the books of Big 6 publishers, who price their books on the high end. Lower prices make books more affordable and more accessible to more potential customers, leading to a virtuous cycle of higher unit sales at higher profit levels which leads to more earnings for our authors and publishers.

- Agency provides our retailer partners a fair, predictable commission of 30%. These retailers are investing millions of dollars – sometimes hundreds of millions of dollars – to attract more readers to more books. They earn every penny. We want them all to build profitable businesses selling indie ebooks.

- Agency creates a level playing field for all ebook retailers. It prevents deep-pocketed retailers or device-makers from using predatory pricing practices to sell books at below cost in an attempt to bleed their competitors’ finances dry, or in attempt to snuff out new competitors before smaller startups gain a foothold in the market.

- Agency forces retailers to compete on customer experience rather than price. Retailers who win will be those who do the best job of attracting customers to their store, and who offer the best algorithms to match readers with books they’ll enjoy reading.

- Agency forces authors and publishers to be wholly accountable to their customers. If the author or publisher prices their book too high, the market will respond by purchasing lower cost alternatives.

As I explained to the DoJ, I think it’s fallacy to believe that agency pricing leads to higher prices. That’s like blaming cars for drunk driving accidents. The driver behind the wheel is responsible. If the Big 6 publishers are pricing their books too high (and I think they are), blame the publishers.

It’s also fallacy to believe that somehow the wholesale pricing model is the savior and enabler of low prices. Under the wholesale model, the publisher has always set the price at which they’ll sell the book to the bookstore, typically a 50% discount to the suggested list price. The $30 front list hardcover you purchase earns the publisher $15, or less. If the publisher decides they need to earn $18.00 on each copy sold, they’ll set the suggested list price to $36.00. If you agree that under normal circumstances, most retailers will not consistently sell all their books at below cost, then it’s reasonable to conclude that even under wholesale, publishers already control the minimum price all customers, on average, will pay.

It’s worth noting that when the Big 5 publishers moved to agency, many of them started earning less per book than they had previously earned under the wholesale model. Pricing control was more important to them.

Analyzing the Short and Long Term Impacts

A return to the wholesale pricing model for ebooks would lead to the following short term affects:

- Indie author and publisher “royalty rates” (earnings) would drop to 35-50% of the retail price.

- Retailers would discount ebooks, and customers would begin migrating to retailers with the lowest prices. In the online realm, the cheaper book is only a click away. Online price checking web sites and apps make it easy for customers to always find the lowest price.

- Authors and publishers, in an attempt to recoup lost earnings, would at first increase prices. For example, if it’s important to a Smashwords author that they earn $3.00 per copy sold, under agency they’d price the book at $5.00. Under wholesale, they’d need to price the book at $7.00, 40% higher. Yes, a return to wholesale could increase prices for customers.

A return to the wholesale pricing model could lead to the following long term affects:

- In the battle for market share, price wars will break out, and some retailers will begin pricing books below cost. Other retailers would be forced to match the prices or risk losing customers. If the price wars persisted, only two or three major ebook retailers would likely have the financial stamina to endure: Apple, Amazon and Google

- Barnes & Noble, which now controls about 28% of the US market, would probably run out of cash and suffer the safe fate as Borders.

- Smaller independent ebook retailers such as the Diesel eBook Store, BooksOnBoard and others, would be probably be forced out of business.

- Formation of new ebook retailers, both here in the US and internationally, would dry up to a trickle, further limiting the number of companies in the business of promoting reading.

- With less competition, retailers would stop discounting, and prices would rise as retailers capture the full 50% margin enabled by the wholesale model.

- With retailing power consolidated in the hands of one or two powerful retailers, authors and publishers could lose control over their distribution options and could be forced to make concessions on royalty rates, or forced to pay co-op dollars or listing fees.

I’m not suggesting that any of these retailers harbor nefarious intentions. They’re simply trying maximize profit on behalf of their shareholders within the environments they operate. As much as I love our friends at Apple, and as much as I hope to be great friends someday with Amazon, I don’t want there to be only two bookstores standing when the post-DoJ dust settles. That would be horrible for everyone, and I don’t think it would even be good for Apple and Amazon.

I think if those of us – including the DoJ, authors, publishers, retailers, distributors, readers – who have the power to promote policies and practices that lead to more bookstores and more reading, we have an obligation to do the right thing. I believe agency will lead to more reading, and wholesale will lead to less.

Ultimately, regardless of pricing model, customers will decide what they will and will not pay.

Here’s the big question: Who should decide what customers should pay? Proponents of the wholesale model believe that publishers make poor pricing decisions, and retailers make smarter decisions. If we’re talking about big publishers, I agree with the retailers. Big publishers are pricing their books too high.

If we’re talking about the indie authors and small presses, I think indies are more savvy about pricing than big publishers. The data above supports this. They’re closer to their customers. With nearly 100,000 Smashwords books to choose from at Barnes & Noble, customers are voting for $2.99 as the median price and our books are priced very near that.

Are retailers better at pricing than indie authors? My guess is yes, simply because retailers have real-time access to store-wide data. But this gap in intelligence is rapidly decreasing. Indie authors are getting faster access to information, and there’s even greater opportunity ahead for distributors such as Smashwords to start sharing more information with both authors and our retail partners. Such information sharing will help better align the interests of authors and retailers, and the end result will be pricing that is more responsive to the needs of customers.

Who Should Control Pricing?

In the end, I think authors and publishers should have the freedom to decide their pricing.

I have no idea how the DoJ will lean in their rumored lawsuit. I also don’t know the negotiation plans of the publishers and Apple. The DoJ declined to share any details of their investigation with me.

I trust now that whatever decision the DoJ makes, they’ll make it with the full knowledge of how it will impact indie authors. As I expressed to the DoJ, indies are the future of publishing.

(Via Smashwords.)

Well, I think that Mark completely misses the point of what is going on here.

It’s not whether agency pricing is good or bad for customers. That has nothing to do with with the investigation.

What IS the point is whether the publishers, and Apple, all got together and agreed, among themselves, on this pricing plan. (Somehow, all the agency pricing publishers “independently” came to the conclusion that their prices should all be the same at the same time. This seems to me to be stretching coincidence a bit.) If this is the case it is collusion and it is specifically prohibited by the anti-trust laws. If they each came to their pricing decision by themselves, without consulting each other, then the Justice Department has no case.

We will see what the facts show (or what the politics of the situation demands. In my experience anti-trust enforcement is one of the most political areas in the DoJ.) The overall public policy question – whether competitors should be allowed to collude to set pricing – is what is involved here.

I should make it clear that agency pricing, by itself, is probably completely legal. It is a form of “resale price maintenance” that we see every day. It is very often seen in high end, or luxury, goods. For example, Rolex and Breitling, to choose just a couple of watch manufacturers, require that retailers sell their watches at the list prices set by them and will pull them from the retailer if it discounts them. This is legal and has been blessed by the Supreme Court.

What is NOT legal is for Rolex and Breitling, as watch-making competitors, to sit down together and say to each other “we will agree with each other not to allow our watches to be discounted”. The facts surrounding the adoption of the agency model, and the sameness of the pricing from all parties involved, and the participation of a retailer, Apple, in the pricing structure, can give rise to an inference that this is just what happened. That’s what the DoJ is looking at.

In the case of the Agency 6 publishers, given their original model of charging the ebook seller half the MSRP of the cheapest print edition, the retailers usually discounted the price of the ebook edition if they discounted the price of the print book. When there’s a mass market paperback edition, the Agency 6 publishers usually set the ebook edition to be the MMPB MSRP, which is higher than the discounted MMPB price and what would have been the ebook price. Because there is no discounting, there is an effective price increase at their lower price point, and sometimes higher than the discounted price of the trade or hardcovers.

In the case of Smashwords authors, most of them are not in competition with the Big 6 authors, they’re in competition with the self-published authors at Amazon who are setting the price at $2.99 because that’s the lowest price at Amazon where the author gets a 70% royalty. If they’re in a different segment of the marketplace, it doesn’t matter what the Agency 6 is pricing their books. An analogy would be if the top 5 automobile manufacturers were to collude on the prices of SUVs, and Smashwords was primarily only selling sedans, it would be irrelevant if Smashword’s position is that the collusion on the price of SUVs didn’t affect prices because the price of their sedans hadn’t gone up, and actually went down because they were competing with the recently introduced Yugo.

Did you do the analyses with ONLY the “big” 6 books? What were the trends then?

I think it’s actually pretty hard to prove that the big 6 raised prices because they never really set the actual price before April 1 2010. With the various sales and discounts one could get at the various retailers, ebooks often were much cheaper, but at the same time, I would see ebooks that had been left at the MSRP of the hardcover even after a paperback was released. For example, with all the sales and store rebates at Fictionwise, I could usually guarantee that I effectively got about 10-30% off any ebook MSRP purchased there, sometimes much more than that.

Bruce, I like your analogy.

The short (and slightly cynical) summary is:

* Agency pricing is good for the smaller guys because the big guys are willing to choke themselves.

* Amazon has too much influence and money, and agency pricing is a tool to fight back. This pricing system makes it much more difficult to run an eBook retailer and form new contracts because of the complicated tax situation and lower margins, but at least Amazon won’t kill the marketplace by undercutting the existing retailers until the competition dies. We can assume that at this monopoly point, Amazon will raise prices and no new eBook retailers will form to increase downward price pressure.

* Authors should take a more active role in marketing themselves, and agency pricing makes them more effective at doing so.

That’s a great article with some quite interesting data. I would point out to Paul Bilba that, although we agree on many things, I’m not as ready to demonize Apple and the Big Six over any alleged collusion as he may be.

Law and lawyers have a bad habit of twisting facts, first one way and then another, picking whichever suits their agenda. Conferring versus collusion is one of those easy to twist facts. “Apple and the Big Six talked about prices,” cue spooky music, “Something evil must have been discussed.”

No, you can as easily say that it was just business. Apple want to jumpstart their iBookstore with as many ebooks from major publishers as possible. That meant talking with them and, being in business, what mattered most to those publishers was their profits. Should we have expected Steve Jobs to have told them that, by signing with Apple and agency pricing, their profits would decline? That’d be nonsense. Even the alleged, multi-party ‘collusion’ fades into unimportance when you realize that Apple needed to make a deal with all of them on the same or similar terms. One company would have gotten very upset if Apple offered another company better terms. That dictates an openness with all the parties.

Independent authors and small publishers wanting to break into ebooks should take a look at Smashwords. In the dog-eat-dog world of book distribution, it’s one of the few companies that’s fully on the side of authors.

Smashwords only real failing is that their book text input is tailored around Word for Windows, as illustrated by their user guides. That’s one of the most dreadful writing environments on the planet. I use it at one of my jobs, and it’s something I wouldn’t wish on my worst enemy.

A lot of writers would be delighted if Smashwords worked with the developers of Scrivener to develop a full-featured, direct-to-Smashwords feed from within Scrivener. The latter is a marvelous writing tool and runs on both Macs and Windows, with an iOS/iPad version under development. Scrivener to Smashwords would be a quick, convenient, almost-perfect writing and publishing platform.

@Paul

Yes, the actual legal case is about whether or not collusion occured, and my understanding is that the investigators are more interested in the “most favored nation” clause then in the agency model itself. But, come on, it’s not about that- it’s about public opinion.

Every day I see people on teleread demonizing the agency model because they automatically equate it to higher prices. Mark is making the very rational point that maybe we should stop doing that.

When publishers and authors compete on price (agency model), the prices actually come down over time because it is very possible for publishers and authors to s-l-o-w-l-y innovate and reduce the costs associated with writing and publishing books.

When retailers compete on price (the wholesale model), we just get an Amazon (or Google- I think if we went back to agency Google could become the new Amazon) monopoly, because there is no way that innovation can reduce the cost of distributing an ebook (it’s free already).

That being said- I’d like to see the data for the average selling price of ebooks on Amazon, not ibooks.

Thankfully what really matters to the US and EU is what is good for the public, and not for the industry people above.

Competition and the principles of competition bring enormous benefits to everyone in society and it is risible and misguided for people to think that being able to bypass those principles is in any way a good thing.

Amazon has been the best thing to happen for the market and for the industry and for writers. Only those with incredibly blinkered minds can argue otherwise.

Michael: I would suggest that you will find that in the views of the US Gov, conferring and collusion will be sen as essentially the same thing. Consider also in the UK when major airlines met to discuss fuel surcharges. The mere meeting to discuss was deemed collusion.

Hi Paul, thanks for running this.

I agree, collusion should be separate from agency, though in the original WSJ story, one paragraph reads, “One idea floated by publishers to settle the case is to preserve the agency model but allow some discounts by booksellers, according to the people familiar with the matter.”

What I read into that is that the DoJ has concerns about the agency model, because otherwise why would publishers consider offering to weaken or dismantle agency if it didn’t provide negotiation leverage? That tells me agency is under the microscope. I hope I’m wrong, but if agency were to allow discounting then it’s no longer the agency we know, and such an outcome could remove the author’s control over pricing. It’s that control I think is worth preserve for the authors. If discounting is allowed, then the next shoe to drop would be lower percentages for authors and publishers.

My hope is that regardless of the outcome, the DoJ not throw out the agency baby (or any its toes or fingers) with the bathwater.

I’m an ebook author with 11 titles under my name so far and three more to go. I’m 100% independent and from the ground up do everything myself. Here’s where this goes in my mind.

I can click my mouse here a few times and watch movies that haven’t been released yet in my country; I can click a few more times and have access to all the free music I want. However, as of yet, from my perspective I’m not aware of a place that I can get a free pirated copy of a popular ebook. Say, “The Hunger Games” for example.

If the DoJ takes a walk and ebook prices are jacked up, I envision piracy becoming an issue for ebook authors just as much as it is for film makers and musicians.

Am I fond of the fact that countless grueling hours, days, weeks, months, and in some cases years of composition, editing, formatting, and marketing are reduced to $2.99 or 99 cents when I believe they’re worth much more? Emphatically no!

I would much rather consumers have a better understanding, or a much fuller awareness of what it takes to be an indie ebook author and pay accordingly. However, the digital age is not complimentary to that because the purchasing is all done anonymously and consumers have nothing to lose by being as cheap as they possibly can. Smashwords data only proves tons of other data all pointing in the same direction, that the ereading community wants to push the price of my hard work to absolute ZERO.

Now for big titles that have sweeping marketing guru’s, algorithms, and experts backing them with money (non of which I have), consumers are willing to pay more because it’s trendy and usually polished to angelic degree’s by expensive editors and digital artists. For the small guys like me, well, along with them I have to compete with content factories.

A part of me wants the prices to go up while another part of me dreads the day it does and the digital pirate ships come sailing into ebook harbor.

21st century technology, and it’s ravenous irrational consumers, don’t seem to give one rip about artists; art in general is being devalued to disturbing levels. If the etailors could raise the prices and in some way ensure protection against piracy I would like to see the standard bottom price of ebooks go to at least $4.99 and stay there.

Thanks

“However, as of yet, from my perspective I’m not aware of a place that I can get a free pirated copy of a popular ebook. Say, “The Hunger Games” for example.”

You be aware of those places, but there are dozens if not hundreds of places like that out there.

“Agency forces retailers to compete on customer experience rather than price.”

You might see this statement as a good thing. I would see it as evidence of wrongdoing.

If you want to run a retailer, then you’re free to start one and run it however you see fit. But these retailers are not your company. They should be free to run their business as they wish. This obviously doesn’t mean they get to act illegally, or in breach of contract. But when the only contracts they are offered by you remove their legitimate choices for running their business — well, that should be YOUR problem, not theirs.

Try this example. I am a small startup, and due to an innovation that I control, I have figured out how to offer exactly the same experience as Amazon, but it only costs me 10% of what it costs Amazon to run their operation. But your contract says I have to price the same as Amazon. So – how do I compete? When a customer looks at me and looks at Amazon, they are going to weigh many factors, including price, experience, and repuation. I don’t have a bad reputation – I just have none at all. The usual approach in such cases is to reduce my prices, which I can afford to do quite easily because of my innovation. That should be a good thing — you still earn exactly what you did before, I make my money, and the consumer gets the same product for less.

It appears that your desire for pricing consistency in the marketplace will tend to reduce the value of my innovative changes in retailing – and that IS a bad thing for consumers.