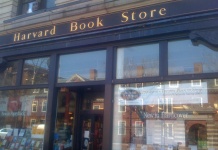

Remember that article by Kristen Lamb decrying used bookstores? One of the people I quoted in my response to that article, Eric Flint, has himself noticed the article and written a response of his own, at length.

Remember that article by Kristen Lamb decrying used bookstores? One of the people I quoted in my response to that article, Eric Flint, has himself noticed the article and written a response of his own, at length.

Flint explains that one of the biggest problems with publishing as a business is that the market is one of the most opaque sales markets in existence.

Most markets crank out goods that are largely very similar to each other, no matter how many different ones there are. Every model of car has more in common with every other model of car than not—they all have four wheels, they all have a radio, they all take you places, they almost all run on gasoline, etc. Every tablet or desktop computer is very similar to every other tablet or desktop computer—they all run one of very few operating systems, they all have similar use cases, and so on.

But every book, song, movie, etc. has to be significantly different from every other. There are simply too many choices—as many as 1.5 million new book titles are produced per year in the English-language market. As a result, most consumers are “very conservative in their buying habits” when it comes to the books they buy—they typically only buy new books by authors they already know. And that, Flint explains, is the crux of the issue: how does someone find out about your books in the first place?

Flint goes on to note that he makes a habit of asking readers he meets how they found out about his books, and the majority of his readers tell him they first discovered him by getting one of his works in a way that did not earn Flint any money itself—borrowing it from a friend, checking it out of the library, downloading it from the Baen Free Library (which he helped pioneer), or, yes, getting it from a used-book store.

He estimates that as many as six people obtain an authors’ book in a way that doesn’t earn him or her any money for every one person who buys it in a way that does. (And he recounts a conversation with author Gene Wolfe, who thought the number was more like ten or twelve to one.)

What’s more, he points out that every author is constantly losing readers who lose interest in his work, or who turn to some other author while no new books are available for that one. As a result, any author who wants to remain a going concern has to work on finding new readers constantly.

That’s why Lamb’s view of the matter is so skewed. She’s right that it’s an either/or situation, but she doesn’t understand that the relationship between “either” and “or” is a necessary and beneficial one.

The way she sees it is this: Either someone buys one of my books in a way that brings me income or I don’t get any income at all.

The way I see is this: Either my little world of income-deriving books is surrounded by a nice thick atmosphere of freebies or nobody reads or buys any books at all.

Grousing about this reality is just silly. It’s the nature of the entertainment business, period. Always has been, always will be. There is a direct relationship between all the different forms in which a given author’s work is distributed. Here it is:

If you sell a lot of books you will get a good income AND

A lot of your books will get passed from one person to another without you seeing a dime from it AND

A lot of your books will end up in used book stores AND

A lot of your books will get checked out of libraries—for which you will only derive income from the library’s initial purchase, not the later borrowings AND

A lot of your books will get remaindered AND

A lot of your books will get electronically pirated AND

A lot of your books will be returned unread with the covers of the mass market paperbacks torn off AND

I go could on. And on. Trust me.

Flint adds, just as he said in the quote I originally used, that he always stops into used-book stores when he finds them, to see if any of his works are on sale and to check with the bookstore owners to find out how well he’s selling. Because if he ever finds out he’s not selling, and he’s not an author whose books they’ll happily buy for resale when they come into the store, he’ll know he’s in trouble.

Below Flint’s post, a number of readers chime in to support his contention—explaining that they first got into his works by reading them free themselves.

It seems that writing and publishing books is a complicated process, and it’s easy to focus on the trees and miss the forest. Flint explains the importance of stepping back and taking a look at the big picture—something that seems to have escaped Kristen Lamb.

Lamb has insisted elsewhere that she’s not against used-book stores—she just thinks that authors shouldn’t be making a big deal out of them and promoting them at the expense of places that sell new books, because by doing so they’re sending potential new-book buyers into the arms of used-book dealers. But what Flint is saying is that promoting used-book stores helps sell new books, because the more your books sell used, the more new readers will discover your works who might be willing to buy other works of yours new later.

Funny, the last email and two letters that I received ranting and raving about my “The Joy of Not Working” were from readers who purchased copies of the book in either thrift stores or used book stores. I took advantage of the letters and email and asked the readers to post a review on Amazon.

Here is the bottom line: I much prefer to have people buy used copies of my books than to take them out of the library. People who don’t buy books tend to be the most negative and give the worst reviews on Amazon.

This quotation applies:

“People that pay for things never complain.

It’s the guy you give something to that you can’t please.”

— Will Rogers