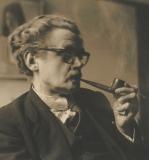

Today, August 11th, marks the birth of Christopher Murray Grieve, otherwise known as Hugh MacDiarmid, one of the greatest Scottish writers of modern times. He was also one of the most fervent and articulate advocates of an unique Scottish identity, and practically the instigator of the modern Scottish Renaissance in Caledonian literature and art. And in this year of the Scottish referendum on independence from the United Kingdom, it’s worth looking at MacDiarmid’s influence on modern Scottish nationalism, and how much he did to help – or hinder – the movement.

Today, August 11th, marks the birth of Christopher Murray Grieve, otherwise known as Hugh MacDiarmid, one of the greatest Scottish writers of modern times. He was also one of the most fervent and articulate advocates of an unique Scottish identity, and practically the instigator of the modern Scottish Renaissance in Caledonian literature and art. And in this year of the Scottish referendum on independence from the United Kingdom, it’s worth looking at MacDiarmid’s influence on modern Scottish nationalism, and how much he did to help – or hinder – the movement.

Politically as well as poetically engaged, MacDiarmid was an early member of the National Party of Scotland (precursor of today’s governing party in Scotland, the Scottish National Party). And yes, he may have been a radical Communist, author of hymns to Lenin, whose association with that movement got him expelled from the National Party of Scotland, but there’s no sign that those sympathies harmed his standing in Scotland, where a more leftward-leaning climate of opinion stretches over a century from the Red Clydeside movement to today’s SNP social justice policies.

More to the point, though, is the Lallans pseudo-dialect that MacDiarmid used to write some of his most important works. He himself described this as “synthetic Scots.” It was absolutely not the language that MacDiarmid (a.k.a. Grieve) grew up speaking. Yes, Lallans did apparently liberate MacDiarmid to write things that Grieve probably could never have – especially the fantastical and sometimes hilarious comic and colloquial touches in A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle. But at the same time as Lallans freed MacDiarmid up, he gave every sign of trying to lock modern Scottish literature down in his own preferred dialect, in an all too typical Modernist preference for a rebarbative semi-private language, accessible in full only to the initiates and the cognoscenti. Ezra Pound did it in The Cantos. To a lesser extent, T.S. Eliot did it (under Pound’s influence) in The Waste Land. James Joyce did it in Finnegan’s Wake – but showed no sign of trying to drag the rest of modern Irish literature down his path.

Unfortunately, that kind of exclusionist, antagonistic attitude wasn’t confined to MacDiarmid’s work. Although he stood for the Communist Party in at least one election (as well as for the SNP in other polls), MacDiarmid not only penned a pro-Mussolini “Plea for a Scottish Fascism” and “Programme for a Scottish Fascism” in 1923, but also, thanks to sleuth work done in 2010 by Canadian academic Susan Wilson in the National Library of Scotland on his correspondence with fellow Scottish writer Sorley McLean, we now know that he was was writing as late as 1941 that he regarded “the Axis powers, tho’ more violently evil for the time being, less dangerous than our own government in the long run and indistinguishable in purpose.” That’s the same kind of thinking you can see in other Modernist writers like Pound.

It’s hard to imagine any point of view further from the modern SNP’s vigorously pro-European, stridently multiculturalist openness. If anything, the SNP has been so fervent in espousing multiculturalism that others have accused it of selling out Scottish identity. I’ve a nasty suspicion that MacDiarmid, if he were around today, would agree with that criticism, right up to and even beyond referendum day. And a more certain suspicion that, despite the comic humanity that runs through A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle, there was a strongly chauvinistic, aggressively exclusivist agenda behind both its language and its inspiration.

It’s also hard to imagine a greater contrast with the warm, broad, humane, playful poetry of Edwin Morgan, who financially and personally did so much, directly, to advance the cause of modern Scottish nationalism. Morgan’s star seems a far better one to guide a new Scotland than MacDiarmid’s.

Still, for anyone who might struggle with following the written text of MacDiarmid’s Lallans, you can hear the author reading the whole of A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle, as well as some other selected works, here. It’s worth a listen – even if it may not inspire you to never speak the Queen’s English again …

Doubtless MacDiarmid would have been closer to the Radical Independence Conference version of Scottish Independence than the Yes Scotland version, but it’s highly likely that he would have criticised both and then, in the event of a Yes vote, found reason to disagree with the independent Scottish state that resulted. A contrary argumentativeness was at the core of the MacDiarmid-persona Chris Grieve created.

It’s inaccurate to align MacDiarmid too closely with Synthetic Scots, though. It largely disappears from his work from the early 1930s onwards. Yes, he had a very public falling out with Edwin Muir when the latter suggested that Scottish writers could write in English, but by this point MacDiarmid’s own work was very much heading this way.

The Scotland that MacDiarmid perceives in the 1920s and 30s (Contemporary Scottish Studies provides a good overview) seems a very different place to the Scotland of 2014, so perhaps the battles that MacDiarmid was fighting — and his approaches — are no longer as relevant. But then again, as T. S. Eliot wrote in “Tradition and the Individual Talent”: “Some one said: ‘The dead writers are remote from us because we know so much more than they did.’ Precisely, and they are that which we know.”