Anyone not just arrived from Mars is probably aware that Scotland is due to vote later this year in a referendum on whether to stay within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, or resume its existence as an independent country. The UK’s Conservative Party, meanwhile, under pressure from the UK Independence Party, has proposed a referendum on whether the UK will remain within the European Union, which might lead to “Brexit” – though depending on the Scottish referendum outcome, that could end up as “Engxit.” Naturally, the issue of national – or trans-national – identity, and what makes it worth being independent or being part of a greater whole, has moved up the current UK agenda as never before.

Anyone not just arrived from Mars is probably aware that Scotland is due to vote later this year in a referendum on whether to stay within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, or resume its existence as an independent country. The UK’s Conservative Party, meanwhile, under pressure from the UK Independence Party, has proposed a referendum on whether the UK will remain within the European Union, which might lead to “Brexit” – though depending on the Scottish referendum outcome, that could end up as “Engxit.” Naturally, the issue of national – or trans-national – identity, and what makes it worth being independent or being part of a greater whole, has moved up the current UK agenda as never before.

Except in one respect: Culture. At least, south of the Border. Scotland, which has made its national celebration the birthday of its national poet, has seldom had any problem identifying culture with identity. But England, as UK children’s author Michael Rosen points out, “is very ambivalent about ‘culture’.” Now, though, English commentators and pundits, casting around for arguments for Scotland to stay within the Union, have turned to culture as a touchstone of shared value.

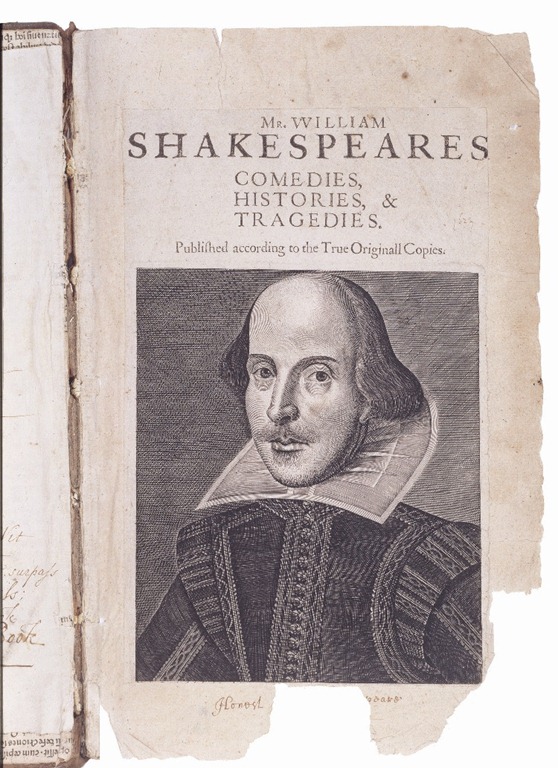

In The Spectator, typically a very right-leaning UK magazine, Daniel Hannan, an equally Brexit-leaning commentator, has penned a piece entitled: “Shakespeare invented Britain. Now he can save it.” His argument commences with the Union of the Crowns in 1603 when James VI of Scotland also became James I of England in a personal dynastic union that joined the two countries under one monarch – although not as an actual United Kingdom until the Acts of Union in 1707. And his thesis is that the Union of the Crowns was: “The fusion of a people already bound together by language, idioms, ideals and a worldview … And in both countries, the biggest single cultural debt is owed to man whose 450th anniversary we are about to celebrate.”

Hannan allows that: “Some Scots … react by asserting a separate literary tradition: their ‘Bard’ is Burns.” But, he continues, “Shakespeare regularly tops the polls as the greatest symbol of both Englishness and Britishness,” and that “The bard … was more struck by the similarities between the two nations than by the differences.”

And ironically, it was a Scot, Thomas Carlyle, who elevated Shakespeare to one of the highest positions he has ever had, as “The Hero as Poet,” in On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History – “the chief of all Poets hitherto; the greatest intellect who, in our recorded world, has left record of himself in the way of Literature.” Carlyle argued that Shakespeare was perhaps the one unifying principle that could hold together all English-speakers everywhere. “England, before long, this Island of ours, will hold but a small fraction of the English,” he wrote. “And now, what is it that can keep all these together into virtually one Nation … This King Shakspeare, does not he shine, in crowned sovereignty, over us all, as the noblest, gentlest, yet strongest of rallying-signs; indestructible.”

Hannan, though, makes a very significant slip: He doesn’t mention any of the great pre-Shakespearean writers who made early modern Scotland arguably the more important literary force in English, at least in the first decades of the 16th century. The makars, especially Robert Henryson, William Dunbar and Gavin Douglas, arguably outshone most of their English contemporaries until the advent of Elizabethan literature further south, and Hannan and other English literateurs still know too little of them.

That characteristic bias shouldn’t obscure the importance of the Shakespeare argument, though. The Scottish independence debate at least has restored Shakespeare – and culture as a whole – to its full and rightful status as a unifying force in the UK. “Will you give up your Indian Empire or your Shakspeare, you English; never have had any Indian Empire, or never have had any Shakspeare?” Caryle asked, and answered. “Indian Empire, or no Indian Empire; we cannot do without Shakspeare! Indian Empire will go, at any rate, some day; but this Shakspeare does not go, he lasts forever with us; we cannot give up our Shakspeare!” Perhaps Scotland will replace the Indian Empire in that statement too. And if that happens, Scotland already has a full-grown, deeply rooted literary tradition of its own to devolve on. But as Carlyle foresaw, if there is anything worth staying in a Union for, Shakespeare is.

I suspect a few survey’s of high school students would find that few know that much about the Shakespeare cannon beyond Romeo and Juliet and perhaps Hamlet. What passes for culture is a fleeting thing, what excited parents no longer excites there young.

That’s no always been true. Folk culture was often the culture of all ages. In a book I did on The Lord of the Rings, I noted that there’s no generation gap in the Shire. The young may get a bit wild, but no one complains about their music because their music is the same as their parents.

Watching historical documentaries on Youtube lately, I did notice that the British (both English and Scot) do seem to have shows about their history from kings to battles. Here, only PBS or a few speciality cable channels cover that sort of thing. The major networks go for the lowest common denominator and a mass audience (that’s shrinking).

When you step into almost pre-history, the English have problems finding something there that’d give them common roots. The original tribes, the Celts, seem to have conquered by Rome. Then, after the Romans left, the Anglo-Saxons slowly pushed them back and in some way imposed their language. The Vikings also made enough visits that my own family tree has about 2% Viking DNA. Then came the Normans with French, and they were pushed out. And each new wave tended to impose its own tales, suppressing the others. The Romans, for instance, hated the Druids so much and persecuted them so effectively that we know almost nothing about them.

Compared to say the Irish, the Scots, the Icelanders, or the Finns, that’s a pretty messy long-ago. You could pick one figure, say King Alfred, to symbolize Englishness. But half or more of the English gene pool comes from people who arrived after him. How can someone say “King Alfred is me,” when his own ancestors fought King Alfred?

All that explains why Tolkien said that he created his own tales about Middle earth to give England a myth much like the Kalevala is for the Finns. That’ll probably never happen. It’s too late for that. And simply picking a nation’s greatest poet for the role certainly won’t work if that poet’s view of life doesn’t work its way deep into their souls.