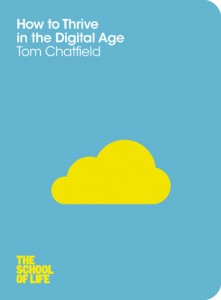

In a recent TeleRead post, I covered some much-discussed comments made by UK writer and media savant Tom Chatfield. He kindly agreed to follow up at length by talking directly about e-books and the issues surrounding reading onscreen.

What follows is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation.

TeleRead: How do you see the advent of electronic publishing and e-books changing the dynamics of print and the relationship of readers to text?

TeleRead: How do you see the advent of electronic publishing and e-books changing the dynamics of print and the relationship of readers to text?

Tom Chatfield: From both a reading and a publishing perspective, the influence of Amazon, Apple and Google is a huge deal, because their overwhelming incentive is to have absolutely everything flow through their “ecosystems”: the more the better.

Instead of filtering first and taking risks, as publishing has traditionally done, the digital model allows people to publish first—and for the filtering process to then be conducted by the marketplace, with successes being tracked by those who own or operate digital infrastructure, and maximized on the basis of live data.

Traditional publishing is almost unbelievably slow and unresponsive in contemporary media terms—which, of course, is part of its charm and value. But this makes it terribly badly equipped to compete with what the big digital players are doing, and will do once they become fully functioning publishing platforms in their own right (as is already happening).

Traditional publishing is almost unbelievably slow and unresponsive in contemporary media terms—which, of course, is part of its charm and value. But this makes it terribly badly equipped to compete with what the big digital players are doing, and will do once they become fully functioning publishing platforms in their own right (as is already happening).

The key thing about reading off screens seems to me to be the basic fact that a screen can have anything on it. It’s not one immutable thing, it’s a single space within which every possible text comes at you. In this sense, every text is in a Darwinian competition for your time and attention, and for your precious single patch of screen real estate—together, increasingly, with all the other media that want to get onto that screen too.

Not all of this is a “bad” thing by any means: The democratization of written words is an astonishing thing, together with our collective capacity for debating and filtering and selecting; and the demand that writing honor obligations of lucidity and readability and appropriate length, rather than see people paid for churning out set-length hunks of waffle because it ticks certain publishing boxes, is a good principle that’s going to get more important.

I do worry, though, about the idea of the book itself shifting away from being a bound, discrete, crafted text—something that is always and only itself—towards something that is a part of the ebb and flow of everything else. I read and think differently about the first kind of text: it helps create a certain kind of time and attention in my life that I value enormously, and associate with high-quality thinking, and the ability in turn to write well and work out what I really mean. I don’t want to let go of this, no matter what format it’s playing out across.

TeleRead: Do you feel there is any real problem with concentration when reading on digital devices? Is this a tradeoff for convenience and access to a far wider virtual library?

Chatfield: There are basic differences between paper and screens that it’s daft to overlook. A physical book has a three-dimensional geography that locates you in its text in quite a different way to anything onscreen: at any and every point in the text, you are always reading in explicit awareness of your location in the book. You know how far through its page you are, where you are on a page; you can flick back at any moment through the geography of pages; you remember and relate to the words differently because of this. It’s not just about the rather boring kind of nostalgia that harps on the aroma of old books—but that does point towards fundamental differences that we shouldn’t laugh away.

Not that physicality is inherently great. I love reading Tolstoy on Kindle, for example, precisely because I lost the daunting bulk (and tiny type) of the physical editions I’ve handled in the past—I find it great to be able to get lost in the present tense a book like “War and Peace,” its episodes and serial nature, without getting hung up on the edifice of the whole—especially because, as the digital edition on my Kindle is the Complete Works, I really have almost no idea how far I am through an individual book within these when reading.

Distraction is not necessarily about individual devices, of course. If I’m reading an old-fashioned paper book—or a book on my old-fashioned Kindle, which does nothing other than show books on its screen—a buzzing smartphone in my pocket can still completely alter the kind of time and attention that I’m giving the text in front of me.

Similarly, I love making notes on paper books, and highlighting digital texts—but I also increasingly like sharing choice quotes via Twitter. It’s a wonderful option to have, and hopefully interesting for other people, but it is also another way in which the crowd has taken up residence in my head.

All of which brings me back to a broader question about the nature and qualities of our time: the kind of time we give to writing in general in our lives. Concentration is best understood in this context, for me: It doesn’t matter if you have a room full of first editions if you have no high-quality time to give them; while it’s perfectly possible to use onscreen services designed for uncluttered, undistracted reading—if and only if you are able to make the time, and deal with other potential distractions.

These are big “ifs,” and made very difficult by the kind of networks we’re all increasingly plugged into, but I’m not deterministic about our relationships with technology—or not quite. The space we have for maneuver can feel alarmingly tight at times: We need good habits to help us, and good spaces. Ironically, it feels like what libraries offer as a space is becoming more rather than less precious today: a place that grants permission to read and think and seek ideas for their own sake, and for your own sake as a citizen rather than a consumer; a space that offers information and access, but doesn’t have an agenda for selling advertising to your eyeballs or for measuring your clicks.

Indeed, much of what we treat as the inexorable “logic” of digital services is just a certain kind of business model, based on advertising and attention; it’s not inevitable or inherent, and alternatives need to be cherished wherever we can find them.

Note: If you’re interested in learning more about Tom Chatfield you can visit his website; follow him on Twitter; watch his TED talk, “7 ways games reward the brain;” or check out his Amazon Author page.