Would you believe it’s been twenty years since they tried to destroy technology? And by “they,” I mean two entirely separate causes.

Would you believe it’s been twenty years since they tried to destroy technology? And by “they,” I mean two entirely separate causes.

In my newsfeed tonight, within minutes of each other, I came across an Ars Technica article (linking to a Washington Post article) marking the 20th anniversary of the newspaper publication of the Unabomber’s manifesto in the hope that someone might recognize the writing, and a lengthy article on The Daily Dot’s “Kernel” section (via The Feature) about the Church of Scientology’s 1990s efforts to “shut down the Internet.” The interesting thing is that, though the causes used such different means and had such different targets, they both shared a distrust of modern technology in common.

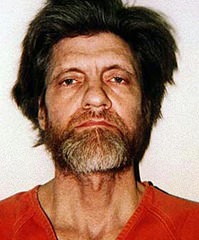

The Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski, was a determined conservative survivalist, whose bombing campaign began in 1978 and lasted for nearly two decades. He’s now serving eight life sentences. The Scientologists were founded by a deceased pulp and SF writer whose grasp of technology was rooted several decades earlier than the 1990s, in which the Internet first began to be used to spread messages debunking Scientology. Both causes tried to fight with the tools they had available to them—be they violence and a rambling manifesto, or flooding a Scientology Usenet group with spam. And both were ultimately unsuccessful in the end.

And both movements came from an era that couldn’t conceive of a global information network.

The Washington Post writes of Kaczynski:

In retrospect, the newspapers “made the right call,” said W. Joseph Campbell, a media historian and American University professor who recounts the Unabomber episode in a new book, “1995: The Year the Future Began.” The major difference between then and now, he said, is that a terrorist wouldn’t need a newspaper to distribute his rantings. As the Islamic State has shown, the Internet has given killers their own publishing platforms. Today, a document such as Kaczynski’s manifesto “would find its way online quickly.”

Though there’s some irony in considering the anti-technology Kaczynski using it to post his message, you never know—the Internet has become so much a part of all our daily lives now that maybe a latter-day luddite might be able to look past its technological basis in favor of its ubiquity.

And in The Kernel, we have this discussion of how the Internet age torpedoed Scientology’s ability to control information:

“I also want to emphasize how much Scientology is about information control,” [Scientology-expert journalist Tony] Ortega says, “And the Internet is the exact opposite of that.” Information control means keeping the church’s secrets, but it also means controlling the stories told by critics. His recent book, The Unbreakable Miss Lovely, tells how in the early 1970s the church intimidated and harassed Paulette Cooper, one of the first journalists to write critically about it. That, he says, was an entirely different time: With limited media outlets to target, Scientology could reasonably expect to control its reputation. Critics could be marginalized or drowned out.

He points to Operation Snow White, a large-scale infiltration of government agencies by Scientology. Eleven high-ranking church members pled guilty or were convicted, including Mary Sue Hubbard, wife and second-in-command to L. Ron Hubbard. In a pre-Internet era, Ortega says, that story could disappear: It was simply forgotten, letting the church “get past it.” That’s much harder today, when the Internet never forgets.

There are those who would say that, despicable as his bombing campaign was, the ideas Kaczynski put forward in his manifesto are worthy of consideration—though they have to to reiterate how reprehensible his behavior was in every other paragraph. (I do believe Fox News protests too much.)

Regardless, anyone who wants to read the Unabomber Manifesto for themselves can find it in a variety of e-book formats on Archive.org. Perhaps that’s the crowning irony for Kaczynski—that his anti-technology manifesto, produced on an old typewriter and which the Post called “perhaps one of the last newsworthy documents to appear only in print” will now live forever on the Internet (or at least as long as the Internet does).

And thanks to the Internet, Scientology has gone from being a powerful and mysterious organization able to control the media message about itself to a tempting target for anyone and everyone to send up. Googling “Scientology” brings up as many or more sites critical of the church as positive ones. The Scientology exposé documentary Going Clear streams via HBO’s on-demand Internet service, not to mention being available on the usual pirate sources if you know where to look.

Has history left them behind? Not yet—at least not in the case of Scientology, which is still a powerful organization, and may well continue for many years. But nonetheless, it’s an interesting reminder that times change, and not everybody is able to deal with those changes.