Tintin, Belgium’s most famous boy comic hero, has long been AWOL from Kindle. You’d think a Spielberg movie would put this to rights, but no. In fact, currently, we’re in a slightly ludicrous situation with Tintin on Kindle (and many other digital platforms). We can get extended Tintin videos on Amazon Video. We can order the DVD of Spielberg’s The Adventures of Tintin. We can get novelizations of the Tintin movie. We can get games based on the movie, for the Kindle. But we can’t actually get comic book versions of the original Tintin stories.

Tintin, Belgium’s most famous boy comic hero, has long been AWOL from Kindle. You’d think a Spielberg movie would put this to rights, but no. In fact, currently, we’re in a slightly ludicrous situation with Tintin on Kindle (and many other digital platforms). We can get extended Tintin videos on Amazon Video. We can order the DVD of Spielberg’s The Adventures of Tintin. We can get novelizations of the Tintin movie. We can get games based on the movie, for the Kindle. But we can’t actually get comic book versions of the original Tintin stories.

This situation has in the past been thanks to the Hergé Foundation, a.k.a. Moulinsart, long presumed to be sole rights holders for the Tintin estate. Moulinsart, which shares the French name for Marlinspike Hall, Captain Haddock‘s ancestral home and Tintin’s de facto residence, has developed a reputation for aggressive litigation against anyone wanting to use the Tintin legacy – for commercial or non-commercial purposes. However, in June this year they had a taste of their own medicine when a court in the Hague found against them after they sued a Dutch Tintin fan group. The trial unearthed a 1942 document in which Tintin creator Hergé apparently assigned the Tintin rights to his then publisher Casterman.

Where this leaves Moulinsart, Casterman, and Tintin himself is still unclear. Moulinsart has apparently launched a challenge to the court’s decision – while acknowledging that Hergé had granted Casterman worldwide publishing rights to the books. “The contract between EDITIONS CASTERMAN and Hergé specifies that EDITIONS CASTERMAN owns the rights to publish on paper and in all languages The Adventures of Tintin. All other rights including the right to exploit separately extracts from the books and other drawings remain the property of Hergé,” states the Moulinsart release. That wording suggests that Moulinsart is still trying to assert control over ebook properties.

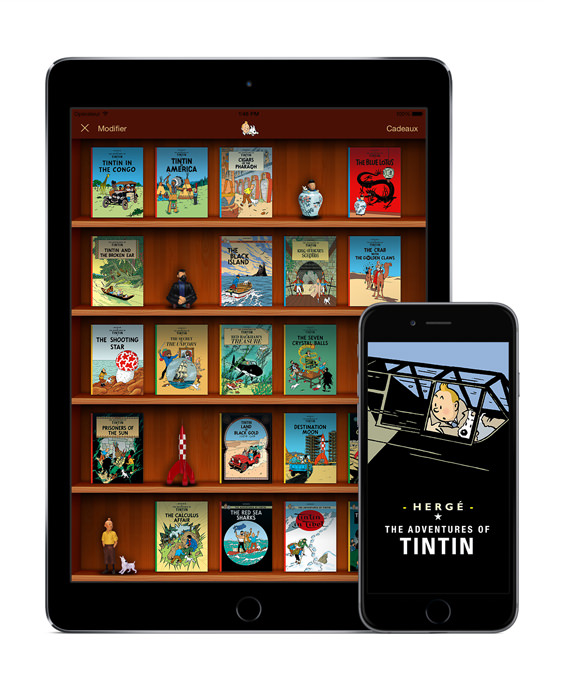

What a coincidence, then, that just a few days before the court in the Hague gave its judgment, Moulinsart released an iOS app to bring The Adventures of Tintin to a hungry (iPhone-using) public. “Moulinsart is proud to announce the first-ever digital Tintin book to be published in English!” proclaims the Moulinsart homepage post. “The release of this digital book is also special as it includes a new translation! The rest of the albums will be published as they are translated. The frequency of publication will be confirmed at a later date.”

In the circumstances, Moulinsart could perhaps have picked a more sensitive, less controversial starting point than the notoriously racist Tintin in the Congo. Besides, their rush to do new translations, when generations of Anglophone kids had grown up on the inimitable translations already in existence, makes one wonder about any rights-related motives about these. Certainly, there’s long been speculation in Tintin fan circles about this.

Did Moulinsart rush a digital edition, with new translations, into print when it got advance notice of the Dutch court’s decision? That seems a conspiracy theory too far. The new translations were first hinted at in spring 2014, well before the court case. The iOS app’s debut concurrent with the court decision seems more like a quick of timing. But it certainly highlights the whole mess around Tintin ebook publication. Moulinsart has announced that an Android version of the Tintin app is still under development, and will appear soon.

Meantime, naughty people will continue to download illicit scans, PDFs, and ebook copies of Tintin books. Links for these can easily be found – though TeleRead won’t share or endorse them. We would urge Moulinsart, however, to get their act together and get the Android version of the Tintin app into Google Play ASAP, and a Kindle version out as well. It’s been too long already – with no apparent good reason.

You’re seeing conspiracies where none exist.

Firstly, the Hague case was thrown out on a really weird technicality – the contract brought up in evidence has never been interpreted by either party to it in the manner the court did, for over seventy years: Moulinsart and Casterman are in accord on that point, and neither side sees that either has gained or lost anything.

Even if the decision isn’t overturned on appeal, it will be a small matter for Casterman and Moulinsart to re-draft the wording in such a way that the status quo of their arrangement prevails.

The iOS app has been in existence for several years now in French, as that language is covered by one publisher; English was promised as soon as possible.

English has been much harder, as there are multiple publishers licensed to produce English-language books (Egmont, Little Brown, Last Gasp and Moulinsart themselves), and the translations in use are copyrighted in the main to Egmont, and even character names (Thomson & Thompson, Cuthbert Calculus, Snowy, Jolyon Wagg, etc.) which differ from the originals don’t necessarily lie with one licensee.

Arrangements needed to be made to allow on-line English versions to be introduced which didn’t impinge on the licensees; presumably Michael Farr needed to find the time to do it.

“Congo” was dropped by Egmont from their list which no doubt made things easier as far as that title was concerned.

So no, no conspiracy…

One interesting point you forgot to mention, that doesn’t necessarily have any relevance to the main thrust of your article but is interesting nonetheless: if you buy the Blu-ray of the Spielberg TinTin movie, you can get a copy of the (standard-definition) digital edition of the movie from Amazon Prime, which you can then download to your Fire tablet. So in a way, you can put TinTin on your Kindle…or at least your Fire—and in that sense, and the sense in which you can do the same for many other titles in one way or another, the movie industry is ahead of the book industry. Granted, the digital copies you can download come with annoying DRM, but e-books have DRM too and you don’t get one of them free when you buy a print book.