Since the ReDigi lawsuit surfaced a few days ago, some of the e-book blogs have been taking notice. EbookNewser simply asks “Could selling used e-books work?” (The answer is, probably about as well as ReDigi’s idea of selling used e-music. In the unlikely event courts bless it, then yes, we might very well see a used e-splosion. Wouldn’t hold my breath, though.)

Since the ReDigi lawsuit surfaced a few days ago, some of the e-book blogs have been taking notice. EbookNewser simply asks “Could selling used e-books work?” (The answer is, probably about as well as ReDigi’s idea of selling used e-music. In the unlikely event courts bless it, then yes, we might very well see a used e-splosion. Wouldn’t hold my breath, though.)

TeleRead has already looked at these issues a couple of times, with a reprint of a post on first sale by Marilynn Byerly and my own look at digital resale efforts that didn’t get off the ground. Fundamentally, digital and resale currently just don’t mix.

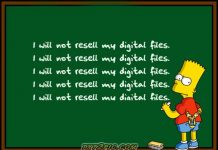

Even if copyright laws permitted the copying necessary for such a resale (which they currently do not), it’s unrealistic to expect people not to try to have their e-cake and eat it too. Just as you can’t make uncrackable media DRM, you can’t really ensure someone is being honest about getting rid of all copies of media he has “resold”. (At least not without stacking restrictions on his computer until it is no longer a general-purpose device.)

Consumers should probably just come to accept that buying digital gives up one of the privileges associated with buying physical, and publishers should price e-books lower to make up for the lost opportunity for regaining revenue from a used resale. That won’t satisfy the people who go around waving the “Information wants to be free” flag, but it’s doubtful that anything realistic ever will.

On the Bookseller’s FutureBook, Martyn Daniels looks at ReDigi and a similar case against music streaming service Grooveshark as well. Grooveshark doesn’t sell used music, but allows customers to upload songs from their own collections and stream them to other people. Daniels has a bit of a different take on the matter, suggesting that having different kinds of resale rights for different levels of media will lead to consumer confusion and corner-cutting, and more disrespect of copyright.

Publisher [sic] be they music, games, ebooks all have to realise that the right to resell is a given and finding a way to allow that is a must. We already have digital rental and loans and restricting or denying resell is just plain lunacy. The resell markets could in fact blooster [sic] the price of the original sale and start to create value added ownership. It could even offer the independent bookstore a digital lifeline. The ebooks and publishing market is a very fragmented and getting consensus of vision let alone action is often a challenge in itself.

As I’ve said before, I just don’t see publishers being willing to open that particular can of worms. Fortunately for them, absent a change in copyright laws (or some really unexpected legal outcomes) they probably will not have to.

Wait. Wait a minute.

“regaining revenue from a used resale”?

One of the most common arguments against the notion of copyright and IP enforcement is that unauthorized copies don’t represent “lost sales” because the people wouldn’t have bought them in the first place, and therefore enforcement based on number of copies is prima facie invalid.

Why doesn’t that same reasoning apply to “used resale”? Who’s to say that the book would have any value at all in the secondary market? I guess you could argue that donating the book lets you claim its value as a tax write-off, but that doesn’t give you actual income.

Eventually publishers won’t have a choice. Let me explain

See, ebooks believe it or not are physical products. They have mass and weight although it is very small and cannot be seen with the naked eye or even a telescope. However the weight and mass of an ebook could be measured with special equipment.

Are ya following me here?

Now, we have established that an ebook is a physical product. Next comes property rights. If I purchase a real product then I own it for the purpose of what I intend to do with that singular product…such as lending, reselling, gifting, etc…

Are ya still keeping up with me?

I’ll let you all figure out the rest of this on your own. Its quite simple really.

I’m pretty sure I’m gonna get flamed for this one…but revolutionaries and reformers usually are.

Rent vs Sell is the key to this discussion. As Heilagr points out, if I buy a copy of something from a seller, it is mine to do with as I please. Even in the day of pBooks, it was possible to photocopy or otherwise transcribe the contents of a book and then sell or give either copy away to someone else. So here I am at a book faire where I have this legit copy of a book up for re-sale or barter. Who is to say that I am infringing by retaining a photocopy? Where does the burden of proof reside? Must I prove my innocence before being allowed to sell this pBook or is that burden on someone else?

Aside from being easier to transcribe or copy, what is the difference between this case of a pBook and the case of someone selling an eBook?

Heilagr and Frank, according to the First Sale Doctrine, with a paper book, you are reselling the paper, ink, and glue, NOT the contents of the book which remain the property of the copyright owner. That means you can’t copy the contents to do with as you please except within the restrictions of fair use. You can’t make a digital copy for resale or sharing. You can’t sell the movie rights or turn it into a graphic novel.

According to the US Government’s definition of ebooks and copyright, the digital version of the ebook isn’t a physical thing that would allow resale.

@Marilynn Byerly No argument with anything you said. The point was that once you buy a copy of a pBook (paper. ink, etc.), it is yours to do with as you please. This is easy to understand in the case of pBooks. The case of eBooks is more difficult because the copy you buy (if that is the correct term, not rent or license) is digital. Technically, you must copy an eBook in order to read it at all. That is, your device must copy it into RAM (Random Access Memory) before it can be displayed in readable form. Clearly, the spirit of copyright law is not to prevent us from reading eBooks that we have lawfully purchased. Equally within the spirit of the law is my right to sell a lawfully acquired eBook — the same copy I purchased and downloaded.

The only point where I cross the line is when I make a copy of the pBook or eBook I bought and then sell off the copy. This is clearly against the spirit of copyright law.

My question was and still is, “where is the locus of the burden of proof?” Is it on the accuser or the accused? The US Constitution, at least, presumes innocence until guilt is proven. This is why “due process” is so important.

Nonetheless, some rights holders would scuttle this fundamental constitutional right so as to assure their bottom line. I, of course, disagree with that position.

@Marilynn Byerly Actually, I do question one thing — the last sentence where you assert the the US government has officially decreed that things not recorded on tangible media such as eBooks cannot be re-sold. I suspect that this is incorrect but perhaps you can cite the relevant statute or official pronouncement of the Librarian of Congress.

Frank, my article on ebooks and the First Sale Doctrine mentioned in the article should answer your questions and give you links to the various government and legal information resources I used. Here’s a link if the one above doesn’t work.

http://mbyerly.blogspot.com/2009/04/first-sale-doctrine-and-ebooks.html

Click on my “copyright” label if you’d like to look at my other articles on the subject.

Most of your worries about having multiple copies of the same ebook within your computer system is just splitting hairs. Publishers and authors have enough problems dealing with large-scale theft to worry with or act against someone who keeps a few extra copies in their private computer and reader hard drives.

@Marilynn Byerly I read your blog post on First Sale and followed the links to the sources and, yet, I see no US government proscription against the re-sale of purchased (as opposed to rented or licensed) digital works. Only commercial rental is explicitly proscribed.

The Redigi case tests the apparently unfounded assumption that eBooks cannot under any circumstances be legally re-sold. I don’t yet see how we can say that it is OK to sell a legitimately purchased copy of a pBook but its not OK to sell a legitimately purchased copy of an eBook. The iBookstore asks me to “BUY BOOK,” not “rent,” “license” or “borrow.” AFAIK, this is the same language used by Amazon, B&N, Google and the rest. Once I have bought a copy of a book, it is mine to do with it as I please according to the First Sale Doctrine. My disposing of that copy in no way infringes the copyright.

Here’s the language of your source (http://www.cendi.gov/publications/04-8copyright.html): First Sale Doctrine refers to the right of a buyer of a material object in which a copyrighted work is embodied to resell or transfer the object itself. Ownership of copyright is distinct from ownership of the material object. Section 109 of the Copyright Act permits the owner of a particular copy or phonorecord lawfully made under the Copyright Law to sell or otherwise dispose of possession of that copy or phonorecord without the authority of the copyright owner. Commonly referred to as the “first sale doctrine,” this provision permits such activities as the sale of used books. The first sale doctrine is subject to limitations that permit a copyright owner to prevent the unauthorized commercial rental of computer programs and sound recordings. (See 17 USC § 2027 and 17 USC § 1098.)

Note that the last link cited is “dead.”

Frank, there are only two ways you can “own” an ebook. The first is if you bought a physical copy of the book such as a CD or floppy. In that case, you own the CD or floppy, but not the contents themselves. The other way is that you bought the copyright from the owner or the owner ceded the copyright to you.

Otherwise, even if the site of the sale uses the term “buy” instead of “lease,” you don’t own that copy of the digital book. It is not yours to resell.

It is also not Google or iTunes to sell since they don’t own the content, they are only leasing it from the publisher or author.

At a vast majority of these sites where they use the “buy” button or the term “buy,” you’ll find in the small print that you didn’t buy the book but leased it so you have no excuse of ignorance in trying to resell something you never owned.

Marilyn, you’re just making this stuff up as you go.

I find a ebook on Amazon, click the “Buy Now” button, a copy of the ebook downloads to my Kindle. I bought it. I own it.

I think you are confused by the fact that most software, which is also digital, comes with a massive “Terms Of Use” that you agree to when you install the package. All kinds of legal crap about not owning and just licensing for use and all that.

But ebooks don’t come with any such contract. I’ve never seen it on Amazon’s website, I’ve never seen it attached to any ebook or to any ereader.

Just because you want all of this to be true for ebooks the same way it’s true for software does not mean it’s actually true without an agreed to contract between buyer and seller.

“I find a ebook on Amazon, click the “Buy Now” button, a copy of the ebook downloads to my Kindle. I bought it. I own it. ”

No, you don’t.

“…ebooks don’t come with any such contract.”

Yes, they do. It’s in the frontspiece of the book, the page that you always skip over. See that line about “all rights reserved”? That’s the contract. That’s the EULA you clicked through (page past?) to obtain access to that work.

@DensityDuck, the validity of shrink-wrap/click-yhrough EULAs is far from firmly established. Like those signs you often see in antique stores (You break it, you bought it), their enforceability is questionable.

The customer is led by the use of the word “buy,” rather than “license” or “rent,” to believe that they are buying a legitimate copy of as copyrighted work, a copy that they hold full sway over. Does the legerdemain of shrink-wrap/click-through EULA licensing change that? Should it?

Don’t tello me it’s raining when … (you know the rest).

@DensityDuck, are you actually claiming that “all rights reserved,” a copyright assertion, is also a contract? If so, what are the terms of that contract?

Let’s look at another real world case, Apple’s iBookstore. Here are the “Terms and Conditions” of the iTunes Store of which the iBookstore is a part. http://www.apple.com/legal/itunes/us/terms.html

This is a great example because so many different kinds of digital products are referenced. As you’ll see, there are things that are rented (Movies), things that are “licensed, not sold” (Software) and things that are sold, not licensed (eBooks, Music).

If you buy a copy of an eBook, you own a copy of that eBook.

What that means in the digital age remains to be seen. Because copies of eBooks are owned, the First Sale Doctrine seems to apply. ReDigi, therefore, is not an open and shut case.

Buying an ebook is no different than buying a CD or DVD. They are all digital. They can all be resold.

The ONLY thing that prevents you from re-selling your used ebook is the DRM which the publishers have unilaterally added to the digital file.

Buy an ebook without DRM. Read it. Then sell your copy and delete it off your device. Perfectly legal and legitimate.

It’s sad to see so many people who are willing to act as shills and stooges for the publishing industry and claim that we don’t have any rights at all.

@Marilynn, I keep coming back to your statement “according to the First Sale Doctrine, with a paper book, you are reselling the paper, ink, and glue, NOT the contents of the book which remain the property of the copyright owner.” I read it, and as I thought about it afterward, I’ve come to the conclusion that either (a) to mangle Dickens, “if the law says that, then the law is a ass,” and/or (b) you really need to speak to someone with actual legal knowledge before spouting off.

Yes, you are selling “paper, ink, and glue,” but only an idiot would believe that that’s all you’re selling. Just as clearly, you are not selling copyright, since a purchaser of an individual book has no right to do that (and is under no illusion that purchasing a copy of a book gives them rights to anything other than that copy).

What you are selling is a purchased “read-right” to that book. I realize that’s not a term that shows up in law, but something like it probably should. Reality tells me I’m right, because the price for the used book is not the price of the materials, but the market value of a used instance of that specific book. There’s a legal market for used books. The notion that you’re selling nothing but “paper, ink, and glue,” is delusional.

I’m not entirely sure why publishers think that they’ve managed to somehow strip that resale right from consumers of ebooks, while simultaneously charging as much if not more, without discussion. But I’m sure it’ll be hashed out in the law, and in the courts over the next few years. Probably not in favor of the consumer, alas.

Writers get nothing from the sales of used books. They will get nothing from the sale of ‘used’ ebooks. Not in their interest to support such a move.

As a consumer I see no reason to enrich third parties. Should the legality of the re-sale of ebooks actually be established there seem no reason to pay for books at all.

Also good luck trying to distinguish between ‘real’ used ebooks and ‘fake’ ones. The possibility for criminal enrichment is staggering. Every pirate a reseller?

I wouldn’t say writers get “nothing” from the sale of used books. They don’t get royalties, true, but they do get exposure to people who might buy subsequent books new if they like them, and the ability to sell used means people know they have a “safety net”: if they buy a book they don’t like, they can recoup some of their investment by reselling it used. That means they’re more likely to take a chance on a new book. A number of authors, such as Eric Flint, or Sharon Lee and Steve Miller, have spoken out in defense of used book stores. (Steve Miller in particular points out that if it hadn’t been for used book stores keeping their work in front of fans after a publisher had given up on them, they wouldn’t have been able to come back years later and put more books out.)

That being said, I don’t think it’s realistic to expect we’ll ever be able to resell “used” digital media. That’s one of the reasons that the publishing industry likes it so much. Copyright laws as written don’t permit it, and given the ease of keeping copies of what you resell I can’t see the publishing industry lobby permitting the passage of any law softening those restrictions. Which is part of why I think that e-books should be priced significantly cheaper than p-books: you can’t resell them to recoup your investment, so that chunk should be taken out of the price up front.

I agree with Chris Meadows when he points out the non-pecuniary value of the used book market to authors and, as well, his observation that publishers are very interested in eliminating this market. However, I have difficulty accepting his assertion that the re-sale of eBooks is disallowed under current US copyright law. Perhaps someone could cite chapter and verse settling this question. I was unable to find any US statute explicitly proscribing the re-sale of eBooks or denying the applicability of the Doctrine of First Sale to eBooks.

Certainly the use of DRM establishes the fact that publishers do not want us to sell, loan or give away the eBooks that we buy from them. However, that hardly has the force of law except indirectly via DMCA. Even there, we have precedent to the contrary. The iPhone, for example, comes with a hardware analog of DRM called a “chroot jail.” Circumventing that mechanism (jail breaking) in order to be able to whatever we want with the thing purchased is now permissible according to a declaration by the Librarian of Congress who is authoritative in such matters.

The media industry has avoided direct confrontations over “first sale” and “fair use” so as diminish the likelihood of legal precedents injurious to its position. Instead, they have resorted to indirect methods and copious quantities of FUD. If we can be dissuaded from contending their wishes, their ideas will eventually become law.

“All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing.” — Edmund Burke (disputed)

These same arguments are used to justify piracy – file sharing for the more progressive.

I wouldn’t say writers get “nothing” from piracy. They don’t get royalties, true, but they do get exposure to people who might buy subsequent books new if they like them, and the ability to read without paying means that people know they have a “safety net” and have lost nothing other than time spent reading.

To a writer it is a difference that makes no difference. I notice that no attempt has been made to explain how to identify genuine ‘used’ ebooks as opposed to fake ones. Theoretically I guess one could resell the same file once, twice, many times?

@alfred complains, “I notice that no attempt has been made to explain how to identify genuine ‘used’ ebooks as opposed to fake ones.”

… which is directly to the point of the question I asked earlier. Upon whom does the burden of proof lie?

Despite the fact that I can photocopy or otherwise transcribe the contents of a pBook, it is highly unlikely that anyone will challenge my right to re-sell that pBook at the local flea market or book faire. Still, it might happen. So who bears the burden of proof if there is such a challenge? In the US there is the presumption of innocence so, clearly, that burden is upon the accuser.

Now switch to the case of a person trying to sell a legitimately acquired eBook.

There, too, it is possible for me to retain a copy of the item I have up for sale, albeit with less effort. Does this ease of copying change the presumption of innocence? I hope not.

It is quite clear that publishers presume us to be a den of thieves. They would prefer Napoleonic law where the accused has to prove their innocence instead of the prosecutor having to prove guilt beyond a shadow of a doubt. I am thankful that this is not the case in the US where I reside.

Given that the burden of proof is on the accuser, the publisher in this case, the question becomes: how can publishers prove that an eBook is not a legitimately acquired copy? This is a difficult but not impossible thing to do. So far, publishers have taken the lazy way out with a “customers rights be damned” approach – DRM.

In the case of Apple’s “Fair Play” DRM which I have studied, I can hand you a copy of an eBook that I bought from the iBookstore but you will not be able to read it because it is tied to my AppleID. I could give you my AppleID and password but that would provide you with access to all of the media that I have acquired from iTunes (songs, albums, movies, applications [MacOS X and iOS] and eBooks) plus my credit card number and its expiration date. Fat chance I’m going to give you all that just to gift an eBook. The only way that I could conscience giving you this eBook is if I could first strip the DRM away.

DRM is an instance of prior restraint. If you circumvent the DRM, you might be accused of violating the DMCA. Assuming that you have not retained a copy of the eBook you seek to re-sell, this basically criminalizes the exercise of your rights under the doctrine of first sale. How clever!

This un-American contradiction is what prompted the Librarian of Congress to make an exception for jail breaking the iPhone and other, similar devices. I see no reason why the same reasoning doesn’t also apply to eBooks.

I also see no reason why publishers with all of the terrifically smart people working for them cannot come up with ways and means to protect copyrights without also trampling on the rights of their customers. That burden is also on the publishers.

@ Frank Lowney

My statement was really a rhetorical one, since as far as I can determine there is no real way to distinguish between an original ‘used’ ebook and a copy. Presumption of innocence or guilt is meaningless in a situation where it would be impossible to distinguish between them. So here you have a business model where it would actually be advantageous to be a lawbreaker.

My second point was that one of the few genuine arguments writers can put forward against file sharing is that it harms their economic interest, in that they are not being compensated for their work. Exactly the same pertains to reselling ebooks – from the point of view of writers.

If this argument is rejected and resale rights is accepted what is to stop me from claiming that file sharing should be legitimate as well. If the writer does not ultimately matter at all why pay for books?

Copyright is not some kind of natural right but a social convention which evolved and depends on certain beliefs, behaviour and even historical circumstances. Absent these and it becomes just another idea whose time has passed.

I am not making any of this up. I am not a lawyer, but I have been a professional author for over 20 years, I’m an ebook pioneer and expert, and I’ve been writing about copyright and “first sale doctrine” issues for over ten years. If you Google these two subjects, my article will be the top result. I am also one heck of a researcher on topics like this that interest me.

All those here who are saying my comments are not correct need to answer this question– What the heck are your credentials on the subject and can you cite government documents or legal articles to justify your own statements like I have?

I thought not.

I would comment on each statement above that is in error with citations to refute them, but why bother since these people didn’t bother to read my article and its bibliography which held that same content?

For those who have read my material, I also suggest this recent article.

http://www.aaronsanderslaw.com/blog/virtual-goods-the-first-sale-doctrine

“I’m a self-appointed expert. And I’ve been a self-appointed expert for a really long time. Much longer than you. Therefore what I say is right and what you say is wrong.”

Sorry Marilynn, but that really doesn’t carry much weight.

The article you linked is on the website of an Legal Firm specializing in Intellectual Property. Gee, I wonder what side of the debate they are on? They make broad statements similar to those that you make along the lines of “When you buy an ebook from Amazon you don’t own it, you just license it.”

Unfortunately there is nothing on the Amazon website, nor in the ebook itself, nor in the purchase process that says anything about licensing or provides any kind of contract or agreement at all.

If you believe that all digital media, or even just all ebooks, are inherently licensed and not sold please point to the relevant section of US copyright law that actually says this. Don’t just link to a bunch of self-serving blather at a Law Firm.

@Binko

You said:

“Unfortunately there is nothing on the Amazon website, nor in the ebook itself, nor in the purchase process that says anything about licensing or provides any kind of contract or agreement at all”

http://www.amazon.com/gp/help/customer/display.html?nodeId=200506200&#content

Is a copy of the EULA you presumably clicked “I Agree” to when you first starting using your kindle hardware/software, and if you look in the Digital Content section it states:

“Digital Content is licensed, not sold, to you by the Content Provider.”

I would expect this sentence or a variant of that sentence to be in the EULA for an commercial eReader/application.