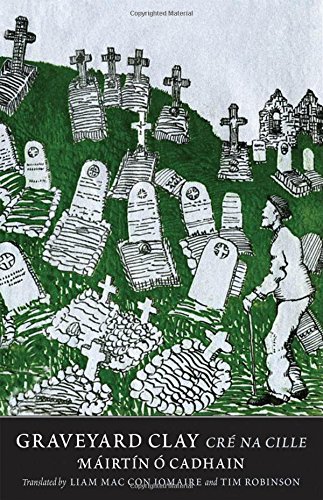

How could a great modern (and modernist) novel from the British Isles become a local cult hit and a contemporary classic, yet languish unread and unknown in most Western countries? The answer is: If it’s in Irish Gaelic. Prolific Irish author and nationalist Máirtín Ó Cadhain (1906-1970) wrote Cré na Cille (variously translated as Graveyard Clay or The Dirty Dust) in 1949, but it had to wait until 2015 to find its first English translation – apparently because the Irish publishers didn’t dare try to find a translator good enough.

How could a great modern (and modernist) novel from the British Isles become a local cult hit and a contemporary classic, yet languish unread and unknown in most Western countries? The answer is: If it’s in Irish Gaelic. Prolific Irish author and nationalist Máirtín Ó Cadhain (1906-1970) wrote Cré na Cille (variously translated as Graveyard Clay or The Dirty Dust) in 1949, but it had to wait until 2015 to find its first English translation – apparently because the Irish publishers didn’t dare try to find a translator good enough.

Happily, the drought is over, with a new translation byfrom Yale University Press’s Margellos World Republic of Letters series this month in hardback and Kindle format. It goes head to head with another translation by

The author would have understood the problem. Máirtín Ó Cadhain was a vehement Irish nationalist in his lifetime, who saw his work partly as defending the cultural identity of his people. He lost his job as a schoolteacher and was interned during World War Two for his membership of the Irish Republican Army, running apparently highly successful language courses during his imprisonment in the Curragh Camp. Scottish Nationalists familiar with the cultural and Marxist nationalism of Hugh MacDiarmid will recognize the type. He was also a prolific short story writer and journalist, penning two more novels as well, so there is plenty, plenty more in store now that the English-language translation logjam has been broken.

And why the long delay? Reports suggest that editors and publishing houses in Ireland were simply scared off by the work’s formidable reputation. In particular, the Ó Marcaigh father-and-son team who held the copyright until 2009 were apparently so wary of finding an adequate translator that they vetoed translation for some three decades. Fortunately for Irish readers, and everyone else, except presumably Danes and Norwegians, the long wait is now twofold over.