The latest Author Earnings report hit a few days ago, and it told some interesting tales—largely, the same tale over and over again. This time, recognizing some valid criticisms of prior methodologies, the Author Earnings crew expanded their crawl coverage to include far more titles than previous AE reports—crawling not just the bestseller lists, but expanding the crawl to also-bought recommendations and each author’s full catalog.

The latest Author Earnings report hit a few days ago, and it told some interesting tales—largely, the same tale over and over again. This time, recognizing some valid criticisms of prior methodologies, the Author Earnings crew expanded their crawl coverage to include far more titles than previous AE reports—crawling not just the bestseller lists, but expanding the crawl to also-bought recommendations and each author’s full catalog.

This resulted in a million-title dataset, and the most thorough look at Amazon sales thus far—a full 82% of daily Amazon Kindle e-book sales. The only titles not included were the very lowest-selling titles on Amazon—mostly, titles that sold fewer than 1 copy per month. They also included 900,000 top-selling print titles and 67,000 top-selling audiobook titles in their catalog, too. The report states:

This is the definitive study of what authors from all publishing paths and all levels of sales success are earning right now from Amazon.com, the largest bookstore in the world.

It captures a complete picture of Amazon author earnings — ebook, print, and audio sales combined— for every single author, traditionally published or indie, who is making any significant Amazon sales today whatsoever.

Author Earnings points out also that over 50% of traditionally-published and 85% of non-traditionally published book sales in the US in any format happen on Amazon.com. This becomes important for when it uses this fact to estimate total earnings for authors based on their Amazon sales.

The report opens with a series of sales charts showing the percentage of e-book unit sales, e-book gross dollar sales, and author earnings by publisher type from February 2014 through May 2016. The interesting thing they show is traditional publisher sales plummeting from 39% to 23% of Amazon unit sales over that time, and indie sales rising from rising from 27% to 44%. Gross dollar sales tell a similar story, though traditional publishers are still taking in 40% to indies’ 25% of gross dollar sales. The market share of author earnings looks about like the first chart, with indie authors earning 47% and trad-pub authors earning 22% by overall market share. I’m not sure how useful that author earnings chart really is, given that those earnings are derived at a second order by applying royalty formulas to the other results, but if the methodology is valid, it does serve to illustrate that indie authors are making more money overall.

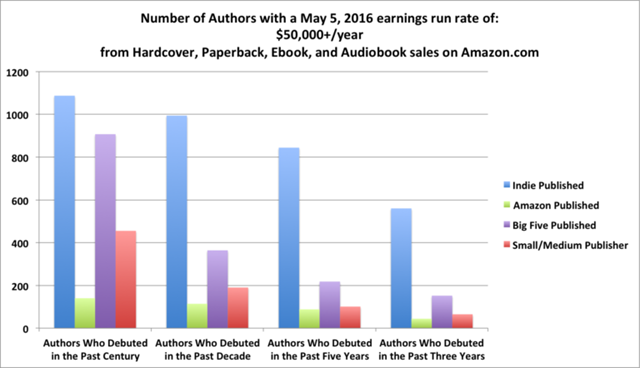

It also seems they’re making more individually. Given that the report is named for “author earnings,” the charts segmenting authors across publisher types by the amount they earn makes up the majority of the report proper. These charts break authors up into those who debuted in the past century, in the past decade, in the past five years, or in the past three years. Then separate charts cover the number earning at least $10,000 per year, $25,000 per year, $50,000 per year, $100,000 per year, and $1,000,000 per year.

The interesting thing is how often these charts tell the same tale. For authors who debuted in the last century, the number of traditionally-published authors making a given amount of money ranges from nearly as many to considerably more than indie authors, as the income rate rises. But in every other category, the number of independent authors earning at a particular level consistently outstrips—usually far outstrips—the number of traditionally-published authors earning at that level. That’s true in effectively every one of the charts.

Another interesting finding was that it turned up a number of high-earning authors who didn’t show up on any best-seller list: 43 authors earn more than $100,000 per year (one of whom earns more than $250,000), 30 of whom (including the top earner) were indie self-pub. 142 authors (105 self-pub indie) were invisibly earning $50,000 or more. Most wrote in genres, especially romance, but there was “a traditional-award-winning indie writer of Literary Fiction” included, too.

All that being said, it’s important to consider what these statistics aren’t. They aren’t a guarantee that if you go into indie publishing right now, you’ll be an instant success, be able to quit your day job, and so on. The way some folks plug self-publishing, they might give you the idea that it’s the next best thing to a dead-certain get-rich-quick scheme. It’s not. Just because a few hundred or thousand indie authors are able to make a go of it, that doesn’t mean you’ll be one of the lucky ones. How many tens of thousands of authors are out there who don’t even make enough to buy themselves a nice steak dinner every now and then?

That being said, unless you can go back in time a few decades and get accepted by a traditional publisher, your odds of success are significantly greater now if you do self-publish—because considerably more self-published authors are making a given amount of money than traditional authors who started at the same time. And that’s even assuming you’re lucky enough to get accepted by a traditional publisher. You’re entering the lottery either way, but you get more tickets for the same amount of writing if you self-publish. Whether you manage to succeed is up to your skill as a writer and how good your luck is. That’s what these numbers say.

It’s also worth pointing out that may put the writing on the wall for traditional publishers. In his own analysis of the report, Passive Guy notes:

The unspoken assumption in assessments of the future of traditional publishing is that publishing will continue to capture the lion’s share of future bestselling authors. If that assumption is false, if most or all of the really talented authors avoid traditional publishers, the future of Big Publishing is bleaker than even the most pessimistic of the industry prognosticators’ public forecasts.

Of course, everyone has to make their own decisions about what way to go. If someone really doesn’t want to do the extra work of publishing their own works themselves, and a traditional publisher offers, it might be worth their while for non-economic reasons to go ahead and leave the driving to them. But it seems pretty clear that, unless the traditional publisher believes it has the next Harry Potter on its hands and will do its utmost to promote it that way, that author’s probably going to be leaving money on the table.

On the other hand, if a traditional publisher does want you, they’ll pay you an advance that you get to keep even if your book doesn’t sell that well. But even getting to that point with a traditional publisher is more than most aspiring authors can hope for—and advances these days for first-time authors tend to be pretty small.

It’s also worth considering that many traditional publishers are picking up self-published authors these days. (Case in point: Andy Weir, whose self-published smash hit The Martian subsequently got trad-published and became a smash hit motion picture.) Indeed, that might be the best reason to self-publish, even if you do want to go traditional—self-publishing a book and getting noticed for good sales will skirt the slushpile gatekeeper, and earn you a little money at the same time. It’s not like the old days, when “vanity publishing” was acknowledged as a scam, and posting your work on the Internet was assumed to be a guarantee that no publisher would ever want it.

Again, there’s no assurance of success no matter how you publish—especially considering how much competition for eyeballs there is now. But Author Earnings continues to suggest you’ve got a better chance going it alone—and that’s going to be a big problem for traditional publishers when it comes to staying afloat.

Excellent article, Chris. Modern authors face a difficult decision. I was offered a book contract by the Little A imprint of Amazon, and the advance was larger than the amount that is usually given to first time authors according to GoodEReader.

The Quote Investigator website was already reaching millions of potential book buyers every year. Many top media outlets, e.g., New York Times, Washington Post, Time, BBC had already linked to the website. Did I need a publisher? The Author Earnings reports seemed to say that signing with a publisher would be a mistake. Yet, Amazon is one the biggest book sellers on the planet. It would have the marketing muscle to sell my book.

After negotiation I accepted the book contract, and the experience working with my editor has been fascinating. Maybe I can write a piece for TeleRead after the book is published.