Christopher Kenneally, Copyright Clearance Center, moderator; John Silbersack, Trident Media Group; Sara Pearl, Trident Media Group

Christopher Kenneally, Copyright Clearance Center, moderator; John Silbersack, Trident Media Group; Sara Pearl, Trident Media Group

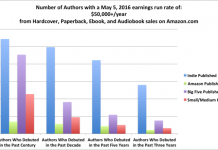

John Silbersack: literary agent. even for major authors electronic book sales only account for a few percentage points. Meeting with ebook companies who want to explain their ebook models almost every week, but still very little money being generated on these deals. Most companies don’t offer an advance but higher royalties. These companies are also selling a marketing platform. Probably not the time to fight the battle about who owns backlist ebook rights because of low monetary value. But it is a battle that will have to be fought eventually. 700 backlist works in the Isaac Asimov estate. How does the agent make them available? Time to try short term licenses and experimentation to find best way. Often these new products will be sold side-by-side with the original book. What makes this content different and takes it out of verbatim rights? For out of print books that have reverted to the author, spending a lot of time now sending termination notices to publishers. For the last 50 years in publishing has been a pretty common practice to use orphan works without permission and put aside some money in case someone comes forward. Not so different than what Google is doing now. For the working writer the Google settlement doesn’t make much difference because can opt in/out. How Amazon take a larger percentage of revenue from an ebook sale than the author gets.

Sara Pearl: lawyer. Amazon thinks of themselves as publishers. Their view is that they are creating a new product. For front list publishers very clear that they keep verbatim rights, for “new media rights” those tend to be reserved by author. Author contributes about 20% of “enhanced” work and a lack of clarity about who creates the remaining 80% and what rights are involved. Cost/benefit to any one author to go ahead with any one of the new projects is pretty small. Very unclear as to how any of these enhanced works fit in with verbatim rights as opposed to media rights. Will eventually have to be litigated. Most of what people worry about the Google settlement is a really small piece. For the average author may mean a few extra dollars. Opt out will probably kill the settlement.

We are doing our first contract for an ebook with a publisher that has carried the books for some years now. I do not quite understand this claus below and am wondering what you may think of it.

Speaking about net income, we mean earnings from a e-book minus publishers’ costs. Under publisher costs – we mean working of the need file format.

Roberta, a good resource for ebook contract info is http://www.epicauthors.com/ . In their article section they have several articles on ebook contracts and the red flags to look for.

EPIC is an outstanding organization, and I recommend that an author interested in epublishing with either a publisher or self-publishing should join for the advice offered by a very experienced membership.

The clause you mention sounds a bit suspicious. Most publishers figure in the cost of creating the ebook into its price so sales pay for it, or the ebook distributor will charge the publisher for the formats they create. The publisher always pays this cost, not the author.

As written, the publisher has carte blanche to add many of his own expenses to the cost of your book so you will see almost no income.

The average self-publishing company has better language than this.

In my opinion, from a business point of view, an author embarking on a contractual relationship with a publisher should personally ‘walk through’ the whole process with his publisher. From his own completion of a title through to the reader receiving it.

The walk through should cover every cost, every expense, every outlay, every expenditure and who is responsible for meeting it. It should cover every single item that is to be deducted from the amount received by the publisher from the reader at the point of sale.

It should cover how exactly the royalty is calculated and on exactly what income figure. It should cover any potential deduction from that royalty, if there is any, before it is paid to the author. It should cover the timing of when the payments are to be made (weekly, monthly, quarterly) compared with actual sales data.

The walk through should also include any other expenditure being incurred separate from being paid out of receipts, such as marketing, and who exactly is responsibly for paying it and if there are any claw back arrangements.

All of this should be specifically set out in any contract imho. Otherwise the Publisher can massage numbers and expenditure and earnings.

Having just read through the epicauthors.com ‘model contract’, and after twenty years of entering into and reviewing and litigating business and corporate contracts, I would never consider using this model contract under any circumstances. It is very poorly worded, poorly drafted and generally very poorly thought out in relation to today’s market conditions. Imho it does not represent the kind of contract I would be looking for when and if I choose or succeed in being in that situation.

I really hope that there are better examples out there for new authors to use as a guide.

Howard, publishing, including the legalities of publishing, is very different from most business models.

More than once, I’ve read of the disasters and problems created when a lawyer who doesn’t specialize in publishing vets a publishing contract.

Your suggestions about what the author should do would be laughed at by a majority of those on the publishing side of the business because publishing doesn’t work the way other businesses work.

The EPIC contract is just a simple model of a contract, but it was written by a lawyer who is also a published author.

“publishing doesn’t work the way other businesses work.”

This says it all to me about the idiotic way much of Publishing is run. What an astonishing statement to make. Publishing is somehow ‘unique’ . . . it is ‘special’ . . .unlike ANY other business. What a nonsense, and what an indictment of a mindset that has become ingrained in this outdated industry.

I just hope authors see what is happening in the new world of electronic publishing and the new publishing industry that is emerging. I just hope they see the nonsense that is spouted about the way things ‘should’ be done and the way things ‘have always been done’ because publishing is ‘different’.

No. Publishing is the same as every other industry. Contracts should be professional. Contracts should be drawn up to the same high standards as every other industry, not in a cozy old fashioned way designed to benefit the publisher and not the author.

I hope authors reject this and demand a higher standard.

Howard, perhaps the contract is poorly worded (and I agree that that all authors should be clear about what exactly they are signing in the contract, and plenty of publishers/agents walk them through it, just maybe not at the Big 6) but are you really suggesting that no expertise is ever accumulated within an industry over time, especially when it comes to the law? I know you’re smug, but come on.

Thank you all for your help and after some research as well i think I may have the Gist of it. The sample contract helped as well so i appreciate having it to view.

Howard, because publishing isn’t run by your idea of a business model doesn’t not make it unprofessional.

And publishing IS different. From the outside, it looks like a manufacturer, but how do you cut costs on production when you can’t ship the author’s job to China or some other cheap labor country? (The printing of the books is done by a printing company, not by the publisher, and they very often do print elsewhere.) A book’s contents aren’t widgets that can be mass produced, or Oreo cookies to be stamped out in mass quantities.

How can you guarantee or even predict profits when a book everyone thinks will make a fortune does nothing, and a book everyone believes will disappear becomes a word-of-mouth megahit? Spreadsheets and market surveys don’t cut it in publishing. Everything is an educated guess.

When the conglomerates bought out the privately-owned publishers, they discovered to their horror that publishing isn’t widget making, and their determination to make it not only profitable but more profitable every year has seen the destruction of types of books that are too niche, the death of indie bookstores, and the ongoing destruction of the writing profession.

On the later, I suggest you read Kristine Rusch’s last three business columns on how the major publishers are padding their bottom lines by under reporting book sales to their authors. http://kriswrites.com/

Sure, publishing does have problems getting past certain traditions as well as a tendency to resist change, but that’s pretty dang common in any industry that is more people than market led.