Time for another one of those posts where I talk about the challenges facing other digital media in order to draw a comparison to e-books. In this case, I will be talking about the comparison of “pirate” media to commercial media, and the conundrum of competing on quality. It will take a little time to work around to how this relates to e-books, but bear with me.

Time for another one of those posts where I talk about the challenges facing other digital media in order to draw a comparison to e-books. In this case, I will be talking about the comparison of “pirate” media to commercial media, and the conundrum of competing on quality. It will take a little time to work around to how this relates to e-books, but bear with me.

This weekend I was at VisionCon, the closest thing to a true SF convention that Springfield, Missouri has been able to host yet. Its guests this year included animé voice actors Richard Epcar and Samantha Inuoe Harte (pictured at left), and one of the things Epcar mentioned during his panel was that animé was having a harder time finding an audience now because online fansub distribution meant that people who downloaded the animé didn’t want to buy the commercial product anymore.

As a long-time viewer of fansubs myself, I had my doubts about this, but upon thinking about it have begun to suspect he might be right—but not for the reasons he thinks. And this was brought home to me when I saw the first few episodes of a yet-to-be-released commercial dub of a recent series—then watched more of it as the fansubbed versions that are still available for streaming at a number of sites on-line. But to understand, a quick lesson in the history of fan-subtitling is in order.

The Origins of Fansubbing

In the early 1990s, when I first got into animé, fansubs were multi-generational VHS copies of animé that someone with a genlock device had copied off of laserdisc onto VHS masters. (Shows could also be subtitled from off-air recordings, but that meant starting with several generations of quality loss, so it usually wasn’t done.) They got translations, then went through and superimposed subtitles over the picture essentially by hand, then people circulated the tapes.

Of course, even then there was a debate over the morality of it. One of my favorite never-ending arguments was the discussion of whether it was “right” to charge copying fees to recoup wear on equipment from copying tapes for fansub requesters. Advocates of the practice pointed out that if they wanted to keep copying tapes, they needed to be able to afford to repair the equipment they used. Opponents seemed to feel it was somehow all right to make free copies of someone else’s work if you were sure to barely break even or even lose a little money in the process, and they argued their cause with all the fire and certainty of college students out to change the world for the better in an incredibly tiny way.

It’s strange to look back on it now, because it really was a different time then. The Japanese studios mostly didn’t care about consumption of their product outside of Japan—they made it for Japan, and really didn’t give a darn whether anyone else liked it or not. But starting in the eighties and really taking off in the nineties when I first came to it, college students seeking something new and different began exposing other college students to animé—and when those first few generations of students graduated, they went on to found animé import studios, importing and localizing it (mainly for the consumption of subsequent generations of college students because most people still didn’t know or care what animé was outside of colleges).

And in those days, by distributing imperfect copies of the shows, fans could build a market for the commercial versions with better subs and much better quality than the hazy, blurry, copies of copies of copies that tided them over until someone could monetize it. And of course most operations stopped distributing their fansubs when said commercial versions were available. Indeed, if it hadn’t been for fansubs helping to build an audience, the American companies could never have existed in the first place. And most Japanese animation studios were pretty tolerant of fansubbing, since they could afford to be—they weren’t directly selling to us, so it was no skin off their noses whether they “lost potential sales” over here or not.

The Digital Present Day

But over the intervening decade or two, a number of things changed. One of them was that animé started catching on as those former college students were finally able to catch the attention of cable networks and big studios, and more American import studios began going into full partnerships with Japanese animation studios, actually co-funding overseas projects with Japanese studios for simultaneous release in America and Japan instead of just buying a license after the fact. And Japanese studios started thinking more internationally once their eyes were opened to the fact that people actually did want to buy their products overseas.

However, by far the biggest change can be summed up in the word digital. Just as the DivX format made it possible for people to rip and share DVD movies over peer-to-peer, it also made it possible to share copies of fansubs. Furthermore, digital TV transmission and hard-drive video recorders meant that shows recorded off the air would be crisp and BluRay-perfect—and the same advances also meant fansubbing could grow beyond merely putting words along the bottom of the screen.

Modern digital fansubbing would make a professional subtitler of the 1990s stare in slackjawed envy. For one thing, they use smooth, anti-aliased, easy-to-read fonts—a lot better than many of the fonts that show up on subtitled DVDs. But that is only the beginning.

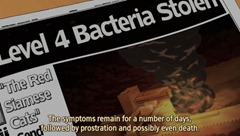

The best digital fansubbing operations, such as the Detective Conan Translation Project, go beyond just translating what is said and in fact translate and replace as much text shown on the screen as is possible, and do it in such a way that it appears the text was put there from the beginning. If a newspaper is shaken or crumpled, the replacement English text moves or deforms right along with the paper. It’s frankly rather amazing—all the more so in that it only takes about a week or so for each new Detective Conan TV episode to get this treatment after it airs in Japan!

The best digital fansubbing operations, such as the Detective Conan Translation Project, go beyond just translating what is said and in fact translate and replace as much text shown on the screen as is possible, and do it in such a way that it appears the text was put there from the beginning. If a newspaper is shaken or crumpled, the replacement English text moves or deforms right along with the paper. It’s frankly rather amazing—all the more so in that it only takes about a week or so for each new Detective Conan TV episode to get this treatment after it airs in Japan!

Are Anime Companies Behind the Times?

And that brings me back to the newly-released (but made in 2009) animé series I saw premiere at VisionCon—one that will not be out commercially for another month or so. The dub was decent work, and didn’t make me cringe the way some dubs had. I wouldn’t mind watching the entire series that way, but for one thing.

And that thing was, it was obvious that the professional company that would be releasing it over here had not bothered even to translate, let alone digitally replace, any text on the screen. Any time characters looked at their cell phone, or read a newspaper, or saw a sign—even one that was important to the plot!—it was left untranslated, meaning that viewers were left wondering exactly what those signs said. (Of course, I don’t know if they were subtitled during the subbed version, since I didn’t see that—but if they translated the signs with subtitles there, they could have used a second signs-only always-on subtitle track to translate them for the dub too.)

Then when I wanted to see how it came out and turned to the streaming version of the fansubs that were out already, I discovered the fansubbers had translated those things. The streaming versions I watched were lower quality, but I have little doubt that if I sought out the originals on Bittorrent, they would be in the same perfect digital quality as the versions that company is releasing commercially. And if I didn’t care about not having dubs, I could probably be satisfied with that.

Of course, animé fansubbers now, as then, usually stop distributing their subs once the series they subtitle are commercially licensed—but nothing ever goes away on the Internet, and even if the subbers stop distributing, other sites will still host the media for streaming and they’ll still float around forever on Bittorrent—as was proven by the way I was easily able to find a streaming version of that not-yet-commercially-released animé with just a little googling. Thus, the low-quality copies that used to serve as a promotion for the real thing are now equally-high-quality with often better localization, and can serve just as well as a replacement for it.

And here is where the e-book comparison comes in, because we’ve heard many complaints about the shoddy quality of editorial proofing for commercial e-books, notably Kindle editions. In some cases it seems as if they were simply put through an OCR script and then posted the way they were. But on the other hand, a lot of pirate scanned e-books have been painstakingly proofread and corrected by the scanners, or by people who got them after the scanners released them. You commonly see “version” notifications on some of the more popular titles, indicating how many times the files have been revised. After all, pirated e-books are released in digital, editable formats, and many people take the time to do just that.

Why are animé companies so far behind the times in the translation work they do? How can an operation like DCTP, made up of fans and hobbyists, produce high-quality localization work that far outshines them? You would think that anything within the capabilities of these fans should be even more possible for a commercial company that built its business and reputation on translating these works. (If not, then it should hire them!)

Of course, DVD players (and, for all I know, Blu-Ray players) can’t show subtitles that look as perfect as the ones digital fansubbers use that are rendered into the picture, and subtitling even signs could be distracting. But there’s no reason these companies couldn’t go in and do the same sort of digital replacement that fans could, on the original media that they then dub or sub. A sign is meant to be read, and a sign in English would probably be less distracting than one in Japanese that would leave the audience scratching its head. It might involve replacing the original Japanese text, but then, it’s meant for viewing in an English-language region anyway.

Of course, DVD players (and, for all I know, Blu-Ray players) can’t show subtitles that look as perfect as the ones digital fansubbers use that are rendered into the picture, and subtitling even signs could be distracting. But there’s no reason these companies couldn’t go in and do the same sort of digital replacement that fans could, on the original media that they then dub or sub. A sign is meant to be read, and a sign in English would probably be less distracting than one in Japanese that would leave the audience scratching its head. It might involve replacing the original Japanese text, but then, it’s meant for viewing in an English-language region anyway.

By the same token, why do publishers continue to let these low-quality e-book scans slip by them? They proofread and edit texts after the authors submit them, after all—it doesn’t seem like the process for proofreading a text after it’s been converted to an e-book should be all that different.

In both cases, these are industries that complain they are having their lunch eaten by pirates—but if they are, it is not simply because the pirates post for free what the industry sells, but because they do a better job of it. It brings to mind Valve founder Gabe Newell’s 2009 keynote about video game piracy in which he suggests that pirates are beating video game companies on service as well as price, pointing out that they have already spent a great deal of money on being able to play the games at all so it’s not as if they can’t afford to pay for quality.

In some cases, as with Detective Conan, there is no commercial alternative—Funimation stopped adapting the TV series (known in America as Case Closed) after the first 130 episodes because it didn’t do well on TV and apparently wasn’t selling well enough to continue.

I wonder if there’s some kind of market opportunity here. I’d happily pay a monthly fee to watch Netflix-style streaming of high-quality animé fansubs (and even dubs, if available) of series such as Conan if it meant that money would go back to the creators of the products. It doesn’t seem to be in the offing, however.

Of course, one difference between the two industries is that proofreading e-books properly doesn’t require anything like the same level of technological expertise as replacing signage. So the only hurdle to clear there is simply sitting down and doing it.

In both cases, the publishers of the media could stand to learn from the people distributing it illicitly. Though it’s not clear whether they ever will.

“I’d happily pay a monthly fee to watch Netflix-style streaming of high-quality animé fansubs (and even dubs, if available) of series such as Conan if it meant that money would go back to the creators of the products. It doesn’t seem to be in the offing, however.”

Eh, you haven’t heard of Crunchyroll? By now they have many of the current series airing simultaneously with Japan (they even invented a new term for that – ‘simulcast’).

P.S. there’s no “é” in “anime”.

No, but there’s one in animé, as originally borrowed by the Japanese from the French dessin animé. It means the last syllable is pronounced with a long “a” sound, just as are other French loan words we commonly use in English that still have that accent mark on it—for example, “résumé” is pronounced differently and has a different meaning from “resume”.

It was printed that way in books when I came to the fandom, and the only reason the accent mark got elided in common usage was because basic ANSI terminals and Usenet, the primary means of communication among the fandom in the ’90s, didn’t support accent marks. But blogs do.

Reading between the lines of your own posting reveals the problem… and it is, as it usually is, a matter of money.

Simply put, of course amateurs and fanbois can take the time to go through digital copies of media, translate and clean them up, and send them back out; they’re not asking anyone for money when they do it. Some of them are already working for a living, some are probably not yet… but they put in time for a labor of love to improve these works.

Contrast this with the originating studio, with their tight budgets, unsure about the future of their industry, and faced with the question of whether they can afford to hire people to subtitle product meant for markets they still don’t fully understand. It’s no wonder Japanese studios haven’t taken to the expensive process of putting subtitlers on permanent staff.

(And believe you me, I’d love to see them do it. The advantage of working with the original material to subtitle and internationalize product would be significantly greater than subbing over material a generation removed from the original, and in some ways impossible to change. My dream is to see Japanese anime made for Japanese markets, then using digital editors to not only translate, but re-sync mouth movements to match the new dialogue! But I digress…)

And to follow your parallel, exactly the same dilemma now has the publishers by the cojones. Knowing they are competing with people who will OCR a Harry Potter book, correct it page by page for free, and push it out onto the torrents, at the same time they don’t feel they can afford to hire good OCR/proofing people to produce a product that they are unsure how much it will profit them.

Unfortunately, the ebook market is in the state of a rocky shoreline battered by waves: Someday, erosion and other natural forces will smooth that shoreline into a beach; but a lot of chaos will result before then. Publishers must work out modern budgets that include the real costs of putting out a good product, then work out how to sell that product to satisfy those budgets. They must be able to compete with fans and free (though illegal) content, and they’ll have to figure out how far they can go legally to protect their content, before they have to swallow the rest and out-sell their free competition with better bargains. That’s a lot of rocky shoreline to batter into submission.

One suggestion to publishers (and anime producers): Try to find a way to leverage all that fanboi work into your product. Money could be the basis of your incentive, but it doesn’t have to be all of it… other offers, such as exclusive content or first-viewing rights, discounts for other products, and actual production credit, could all contribute to a better product, sold legally. I’d imagine a lot of people would be satisfied enough with the bragging rights (or credit on a resume) of seeing their name listed as “production contributor” (or somesuch) on a popular ebook, especially as it might lead to other opportunities.

A book I read not long ago (I’m still trying to find it) makes clear one aspect of the “illicit” and underground movements of popular culture: At some point, when they become popular enough, their creators find ways of making their product legitimate, becoming legal, forging a new above-ground industry out of it, and usually turning a legal profit in the process. The only thing stopping them is making the initial steps of cooperation and collaboration that will bring the two groups together and legitimize their operations. In terms of ebooks, we still have that to look forward to.

Found the book: Matt Mason’s “A Pirate’s Dilemma – How youth culture is reinventing capitalism.”

Although the book describes cultures that created their own products/movements based on pirating other people’s works and turning it to their own advantage… reading between the lines reveals how each of those movements eventually gave enough power to their creators for them to find ways to legitimize and monetize their new creation, essentially becoming new versions of the same capitalists they originally railed against… they became their worst enemy, and often found themselves eventually fighting new pirates attempting to do what they themselves did to get ahead.

In other words, the book describes the incredible irony of pirates: The fact that the most successful pirates eventually end up as capitalists, and are usually the most vocal attackers of other pirates.

A lot of publishers farm their proofing / copy editing out overseas now to companies in India. I used to work for one that had a branch there that did it. I’m not in the least surprised at the slip I’ve seen in book quality in the last decade.

Of course, small ebook firms don’t usually even have that option. I’ve heard any number of ebook authors say that they’re expected to do their own quality control, because some ebook publishers just don’t want to pay someone else to do it.

But for all of that, most ebooks I buy via Kindle are still better than the typical pirated copy. Some very popular pirated books are well-proofed. But most are not. So I pay for my ebooks if they’re available, even though their quality could be improved too.

Re: untranslated text on anime, it drives me to seek out fansubs just to avoid the headache of pausing and trying to translate it on my own. It real detracts from my viewing experience. At the very least they could use a sign subtitle track. I really appreciate companies that include that.

@Chris

Ah yes, the fabled French connection. I personally find it extremely implausible, since most of the animation itself and related terms (e.g. “animeeshon”) was imported from the U.S. (Disney etc.), not France. I think “animé” was common in the 80s because most people wouldn’t know how to read it properly, so the accent was put on the last syllable to make sure of pronunciation. It’s similar to the word Pokémon, which I don’t think you can argue was imported from French 🙂 These days “anime” a pretty common word so no accent necessary – check Wikipedia or any online dictionary.

@Steven

“At some point, when they become popular enough, their creators find ways of making their product legitimate, becoming legal, forging a new above-ground industry out of it, and usually turning a legal profit in the process.”

That’s what happened with Crunchyroll, basically. See here.

BTW, I can relate such experience as well. A couple of year ago I released a fansub of The Girl Who Leapt Through Time (a wonderful movie – highly recommended). The company that licensed the movie in Russia has approached me and asked to use my translation in their release. I did not get much money out of it, but I was happy that my translation was used. And it seems many people liked the translation very much 😉

Steven: As it happens, I reviewed that book. 🙂

Chris, while I often draw comparisons to anime (I used to freelance in the industry) for ebooks, I think you missed the mark here. Fansub quality is not what’s made people prefer them to DVDs. Replacing text as you suggested has been tried, but with the results that people screamed bloody murder. It’s manipulating the original artwork, which is a no-no for the fans who are serious enough about their fandom that they’re willing to pay for content. Any text in a show that’s relevant will be subtitled using a signs-only subtitle track instead. If subtitles weren’t shown, the text was either not relevant or they were turned off.

Instead I’ll try to sum up the more relevant factors for the business hurting:

– availability. Say it three times, or heck pull a Steve Ballmer. It takes a minimum of half a year from the ink is dry on a contract before you’ll see a localized DVD on shelves, often more. Digital fansubs are usually available within a week of a show airing in Japan. In addition the DVDs (or even legal streaming) are usually region locked and are mostly distributed in the US. There are some localization studios in other countries, but they still have limited distribution. Some shows also don’t come out outside Japan at all. It’s faster and easier to download than to find a DVD in a local store.

Now compare that to ebooks – you have region limited sales, DRM and windowing of releases. This leaves a very obvious space for piracy to enter

– the niche market. Anime is an extremely small market and is thus more vulnerable piracy. A good selling title hits 5 figures. This means that for the big titles, fansubs don’t make too much of a dent, but for small titles, not many people are going to want to double- dip for a mediocre show after having watched a downloaded version

For ebooks you can draw a comparison to authors like Stephen King and JK Rowling. Though they’re losing money to piracy, they’re raking in the big bucks from paper copies to a point where pirated content is not even close to affecting profitability. Authors with a more limited market may be more vulnerable to piracy

– price. It becomes harder to compete with free, as more shows become fansubbed, giving people more choice. Competition drives DVD prices down to minimum, with the result that profit margins are lower than ever, increasing financial risks

– the fad faded. Let’s face it – part of the reason anime did so well for a while was because there was a fad effect going. People grew out of it, and the market shrunk

– Musicland bankruptcy. The US anime studios lost a lot of money due to this, and only the biggest ones managed to survive

– bad financial decisions. Several companies in the anime localization business have gone under with the result that less shows are available, less money goes back to Japan, and thus less shows are made with a more international appeal. Availability of quality licensed content goes down

All this comes down to the anime market in the US having a bit of a crash, and it’s never really recovered. You can’t increase prices to previous levels for instance, and especially not with everything still being available on fansubs. There’s no way to pull an agency model equivalent. Some companies have tried with higher prices, and their titles simply don’t sell. People have too much entitlement syndrome and have become used to low prices.

Fansubs were a contributing factor to this, but it’s by far the only one. There’s been more awareness about it however as the industry tries to influence fans to pay instead of pirating, since it’s largely an issue of ignorance and attitude.

—

Incidentally, while you would think that people would want “high quality” and thus buy DVDs, this doesn’t really hold for anime. This is easily proven by people being happier with a lower quality encode and worse localization – most fansubs are still riddled with translation mistakes for instance which people don’t notice. They’ve come quite a ways from the VHS fansubs, but they’re not the quality that you’d get from a professional release – they’re simply “good enough” quality that not that many people want to wait for a DVD release and then pay extra for it to boot.