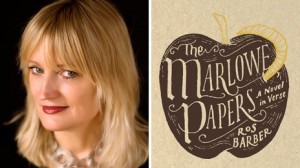

I spoke to Ros Barber, poet, former computer programmer, and now historical novelist, about her blank verse novel “The Marlowe Papers,” awarded the UK’s £10,000 [$15,223] Desmond Elliott Prize for new fiction, and about the difficulties and rewards of writing in verse.

TeleRead: What’s your view on the position of verse in current literature, both as standalone lyric and as a medium for longer or different work?

Barber: The majority of the reading public have an aversion to reading verse. Enjoyment of poetry (which children naturally love) is routinely destroyed in the course of a school education.

Barber: The majority of the reading public have an aversion to reading verse. Enjoyment of poetry (which children naturally love) is routinely destroyed in the course of a school education.

There is a general perception of poetry as either difficult, dull, or trite. And it really doesn’t help that there’s a lot of difficult, dull and trite poetry out there. There’s also some brilliant poetry, in all genres—but the audience that seeks it is small.

am heartened by the enormous audience that gathers annually for the T.S. Eliot readings at the Royal Festival Hall, but most poetry events struggle to fill thirty chairs. Book sales for most volumes of (even rather good) poetry remain in the low hundreds.

So the position of verse in current literature is (in general) on the sidelines, unloved and barely noticed. In the UK there are perhaps five well-known living poets. To be a truly successful poet, you have to be dead. There is barely a place in the literary world for the contemporary stand-alone lyric—unless you’re a talented musician and prepared to sing it. And everyone told me from the outset it was madness to write a novel in verse, when there is so little chance of overcoming people’s understandable prejudice.

If you must write a longer verse work, it’s probably best to write for performance, as poetry always plays better in the ear than the eye. Poetry’s fusion with rap—see Kate Tempest‘s Brand New Ancients – offers verse the glimmerings of a possible popular resurgence. But I’d be surprised if poetry can really overcome its tarnished reputation, unless schools stop killing it.

TeleRead: Did your initial training as a programmer have any influence on your writing? On your approach to publishing and e-books?

Barber: No, not really. My training as a programmer stemmed from an aptitude for logical thinking, and perhaps this logical thinking is sometimes also applied to the way I write or to my enjoyment of poetic form. But being a programmer was just a way of earning my keep while I served my writing apprenticeship.

Being computer literate has been pretty helpful in other aspects of writing, such as setting up my website. But most of that stuff – including e-publishing—is extremely user-friendly these days. I’m currently writing and publishing a non-fiction book via leanpub.com and the platform pretty much does the whole thing (apart from the writing!) for you.

TeleRead: How do you combine historical research and the adoption of a period voice (especially in verse) with narrative drive and plot?

Barber: This question should probably be in the past tense! I can say how I did them separately but not really how I combined them, since that part just happens.

For the research I read/watched/listened to the entire works of both Marlowe and Shakespeare and various works by other writers of the period, to get a feel for the language, and read secondary sources (the work of historians and other scholars) to a get a feel for the time. The period feel for the voice came from immersing myself in the DVDs of the BBC Shakespeare series during that first year, often just listening rather than watching.

The verse is something I already had a lot of practice in and was the easiest part of the book: Once you have the rhythm of iambic pentameter in your head, it’s actually hard to stop writing/thinking/speaking that way.

Narrative drive and plot was helped by the fact that I had a lot of story to cram into a small space: I didn’t want the novel to be much longer, word-wise, than a Graham Greene book, but Marlowe’s life and theoretical afterlife were eventful. The compression of poetry helped me make fairly rapid shifts between different points in the action, and tighten the narrative drive.

TeleRead: How was it writing such a work as your debut novel? Did your experience as a published poet help?

Barber: I had no idea it would be my debut; that it would ever be published. I hoped, of course—but was aware that I’ve hoped before with limited results! That it has become my debut is great: impact is important, and the fact that it is written in verse but reads like a thriller is what has attracted the most attention.

My experience as a poet was essential to making a good job of it. A ten-page narrative poem about the Nore Mutiny of 1797 made me realise I loved writing first-person narratives based on historical research, and many years of writing sonnets and other poems in iambic pentameter stood me in good stead for pulling off the form.

A creative skill must be practiced and honed to quite a degree if you want to use it to do something out of the ordinary. It’s good to know that I have finally served out my apprenticeship.

I have had a copy of The Marlowe Papers in my TBR queue for a long time; after reading this blog post, I’m placing her new novel in my watch list.

However, if she had self-published, there would be little to no chance my reading the books. I just don’t read self-published books. When the fad was new, I heard about all these great books being self-published, and I tried reading a few. They were mostly bad, some truly beyond bad, and a few meh. It was all marketing hype and lies. Yes, there may be a great self-published book out there somewhere, but the odds of me finding it in the sea of trash is slim.

Good authors will stick with traditional publishing. Ros Barber made the right choice.

In that case she must be a bad author, because she also self-publishes.