In a recent article in Futurebook, the digital offshoot of Britain’s The Bookseller, Tom Chalmers takes issue with the sale or return policy, calling on booksellers to, “scrap this ludicrous, self-defeating, damaging way of doing business.”

In a recent article in Futurebook, the digital offshoot of Britain’s The Bookseller, Tom Chalmers takes issue with the sale or return policy, calling on booksellers to, “scrap this ludicrous, self-defeating, damaging way of doing business.”

Hold on: Jettisoning a pillar of the book trade: the return of unsold books to the publisher free of charge?

Does that make sense?

Well, Chalmers makes it make a lot of sense. And I happen to agree with much of what he says. “Having started my first publishing business eight years ago, I can say with complete certainty that if we were able to give books back to the printer that we didn’t sell, we would not still be in business. Finished. Gone. Dissolved,” he asserts.

The reason? Bookselling should be about selling books, not stocking books that might sell. Any business mechanism that disincentivizes booksellers from selling books is harmful, no matter how tempting it looks.

The reason? Bookselling should be about selling books, not stocking books that might sell. Any business mechanism that disincentivizes booksellers from selling books is harmful, no matter how tempting it looks.

Chalmers isn’t the only one to make the connection by any means.

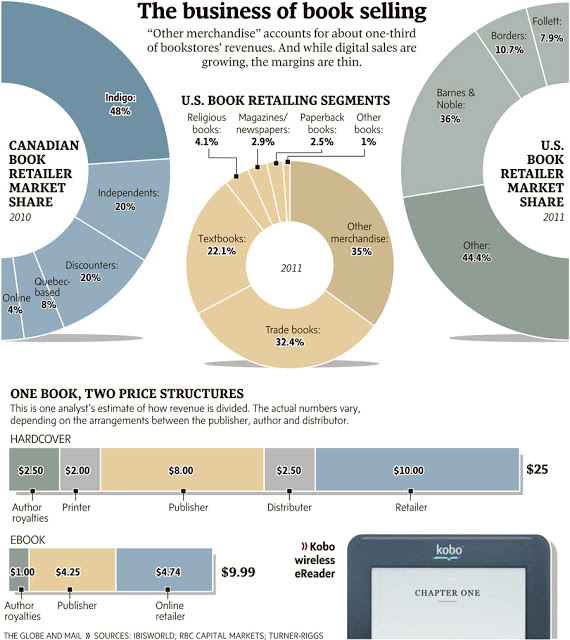

David Gaughran, in his self-publishing bible “Let’s Get Digital,” points to sale or return as one of the key structural challenges facing the publishing industry—a stopgap policy during the Great Depression that got institutionalized and has been distorting the business ever since. “More than half of the books that publishers print are returned,” he points out.

As someone who worked in a book packager, and independent as well as mainstream publishers, I can tell you that many books on shop shelves or in warehouses owe their existence to ego, personal ties, gaping holes in series or lists, vanity, laziness, silliness, or sheer whimsy—all without serious consideration of what readers want.

The book trade just has not had the market discipline imposed on it to develop efficient market demand prediction, and sale or return is one of the obfuscating mechanisms. Publishers are churning out books that won’t sell: Why should booksellers have to nurse them for a while?

“As the looming online threat has grown and sunk its teeth in, we have moved away from rather than towards proper bookselling, which has been disastrous,” Chalmers continues. “We have tried to compete on price rather than on our trump card, the one thing the online retailers won’t and don’t do—hand selection of the best new books.”

Chalmers advises independents not to waste their effort on the bestsellers that publishers are keen to promote, but rather choose the books they want to sell and that they know their clientele will buy. And then sell them, rather than go on the assumption that half will go back unsold.

Given the travails of the UK independent bookselling sector, it’s unlikely that the Booksellers Association or anyone else in the trade will get behind an initiative to relinquish any business advantage, however slender. But Chalmers’ argument ought at least to provoke some thought among booksellers about what they should be doing and what they are there for.

No one wants to be the one left sitting on a pile of unsold stock, paid for or not. And any business practice that leads to that needs to be looked at hard, right? Chalmers’ platform of individual book selection sounds a more convincing rationale for booksellers to remain in being than many others I’ve read lately.

I can’t help thinking he’s starting at the wrong end of things. Instead of saying, “Hey booksellers, stop ordering books you know won’t sell,” maybe he should say, “Hey, publishers, stop printing books you know won’t sell.”

And as a publisher himself, it seems a little disingenuous. “Hey, bookstore guy. Stop taking advantage of our generosity. No, really, stop it.”