Here’s the second section of my draft of a book chapter for a book edited by No Shelf Required

Here’s the second section of my draft of a book chapter for a book edited by No Shelf RequiredWhat does Open Access mean for e-books?

There are varying definitions for the term “open access”, even for journal articles. For the moment, I will use this as a lower-case term broadly to mean any arrangement that allows for people to read a book without paying someone for the privilege. At the end of the section, I’ll capitalize the term. Although many e-books are available for free in violation of copyright laws, I’m excluding them from this discussion.

Public Domain

The most important category of open access for books is work that has entered the public domain. In the US, all works published before 1923 have entered the public domain, along with works from later years whose registration was not renewed. Works published in the US from 1923-1963 entered the public domain 28 years after publication unless the copyright registration was renewed. Public domain status depends on national law, and a work may be in the public domain in some countries but not in others. The rules of what is in and out of copyright can be confusing and sometimes almost impossible to determine correctly.

In addition to public domain books that are made available by Project Gutenberg, works digitized by other efforts may be available on an open access basis. It’s not true, however, that any digitized public domain book is also open access. That’s because the digitizer can restrict access to the works using license agreements. For example, JSTOR has many digitized public domain works included in its subscription products, but the terms of the subscription prevent republication of their scans. Similarly, Google puts restrictions on the public domain books from partner libraries that it has scanned, digitized and included in Google Books. While they’re available for free, there are limits on what you can do with them.

The public domain is more than just free; it belongs to everyone. Public domain works can be copied, remixed, altered or extended. A book publisher can take a public domain text, print up bound volumes, and sell them in bookstores. A movie producer can create a cinematic dramatization of the public domain work; derivative works such as the movie acquire copyrights of their own and are not in the public domain.

Free Copyrighted Content

Laypeople often confuse public domain for “free”, and vice versa. Most content available for free on the web is copyrighted, which restricts what people can do with it. Often, the content is made available using an advertising model, trading the opportunity to read and interact with content for the user’s attention to ads or links to e-commerce websites. But website users are usually not free to republish content or email the content to friends beyond the bounds of fair use. They’re bound by whatever terms and condition the website chooses to employ; if there are no explicit terms and conditions, they still can’t copy the website’s content for other uses.

Even professional publishers are sometimes confused by copyright on the web. In 2010, the editor of “Cooks Source”, a Massachusetts magazine got into hot water for republishing a blogger’s work without permission. The publisher’s response to the blogger, on being asked for restitution, made the rounds of the Internet, and is striking for the bellicose ignorance it betrays:

Yes Monica, I have been doing this for 3 decades, having been an editor at The Voice, Housitonic Home and Connecticut Woman Magazine. I do know about copyright laws. It was “my bad” indeed, and, as the magazine is put together in long sessions, tired eyes and minds somethings forget to do these things. But honestly Monica, the web is considered “public domain” and you should be happy we just didn’t “lift” your whole article and put someone else’s name on it! It happens a lot, clearly more than you are aware of, especially on college campuses, and the workplace. If you took offence and are unhappy, I am sorry, but you as a professional should know that the article we used written by you was in very bad need of editing, and is much better now than was originally. Now it will work well for your portfolio. For that reason, I have a bit of a difficult time with your requests for monetary gain, albeit for such a fine (and very wealthy!) institution. We put some time into rewrites, you should compensate me! I never charge young writers for advice or rewriting poorly written pieces, and have many who write for me… ALWAYS for free!

Many free e-books are available on a similar basis as free websites. They may include advertising or advocacy. Promotional literature and instruction manuals often fall into this category. Many publishers make free e-books available for limited periods of time as a means of marketing them; that doesn’t make them free to redistribute, though it happens.

Creative Commons Licensing

Creative Commons licensing arose to expand the range of creative works available for others to build upon legally and to share. Many authors really want their works to be redistributed for free in venues such as Cooks Source, but they want to make sure attribution is given, and often want to prevent their work from being altered or chopped into pieces. Others want to make sure that if their work is altered or somehow improved, the altered or improved version will also be available for free. Sometimes, authors are happy to have their works reused non-commercially, but want to keep their works from being commercially exploited without permission. Creative Commons licenses give authors the tools they need to accomplish these goals.

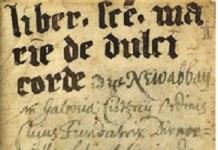

|

| CC BY-SA mark |

The different licenses available from Creative Commons are designated with a special mark, with added code letters that indicate the features invoked by the rights holder. For example, the “Attribution-ShareAlike” license is denoted by the letters “CC BY-SA” and the mark shown. This license requires attribution as to the author of the work, and the ShareAlike features bind the licensee to share any modifications or improvements.

It’s important to note that in the Creative Commons licenses, the owner of the copyright does not give up ownership of the work. The owner is free to re-license the work under any terms they desire, and can still sue people who infringe on the copyrights. The owner licenses the work to the user, who accepts the license as a condition of use. The user can in turn distribute the work along with a copy of the license to other users, who accept the terms of the same license from the copyright owner as a condition of their use.

Creative Commons licensing is now widely used for free e-books distributed on the web. Perhaps the best known e-books using CC are the works of Cory Doctorow, a blogger, science fiction author and advocate for copyright law reform. It’s also used for Wikipedia contributions, and is supported by Flickr for use in photos.

Copyleft

While Creative Commons licenses are the most frequently used for e-books, other licenses can be used to allow for the free reading of books. Noteworthy among these is the GNU Free Documentation License (FDL), created by the Free Software Foundation to allow software documentation, manuals and other text to be distributed with strong “copyleft” provisions compatible with the GPL software they’re meant to accompany. The GNU FDL can easily be applied to e-books; many ebooks have been released with this license and with other Free Software Foundation licenses.

The idea of copyleft is that licenses can be used to prevent someone from taking from the commons without also giving back. For example, when a book publisher adds commentary and illustrations to the text of a Shakespeare play, the resulting book is covered under copyright and permission must be given for redistribution even though the underlying work is in the public domain. This would not be allowed by a copyleft license. The Creative Commons SA licenses have weak copyleft; the GNU FDL is stronger, and even forbids the use of DRM. It’s not clear whether it would be legal to distribute a GNU FDL e-book to a Kindle e-reading device without permission from the author.

Open Access vs. open access

by Phoebe Ayers, Charles Matthews, and Ben Yates. Is it an open access e-book? Based on the page at the Free Software Foundation, you might assume the answer is an easy yes, because it comes with a GNU FDL license. If you search for this book on Google, however, you’ll have to dig quite a bit to get a free e-book. Amazon will sell you the Kindle version for $21.64. You can buy it in three different formats from O’Reilly or from No Starch Press, the publisher, for $23.95. Google books has it through their publisher program; it appears to fully available and Google doesn’t try to sell it to you. You can find the e-book in a library through Worldcat, but the libraries that hold it restrict access to their own users. Wikipedia itself has a page for it, but no download link; for that you need to look on the talk page.

The intent of the publisher of this book doesn’t seem to be to make the e-book available openly, even though it uses a “free” license. The free distribution of the e-book is not effective. There are a lot of ways to license content, but at the end of the day, it’s the intent of the rights holders and the effectiveness of the free distribution that makes an e-book “Open Access” with capital OA.

Notes:

- How Wikipedia Works: is available (GNU FDL license) as PDF (here (15 MB)). The Google books version is here. It’s listed on a GNU web page.

Via Eric Hellman’s Go to Hellman blog

I’m not sure why Part 2 is here while Part 1 was at No Shelf Required, but assume that you are still looking for comments…so I have three comments: 1. I do not think the lengthy quotation beginning ‘Yes, Monica’ adds anything to the section and it sits slightly uncomfortably in the text – both as the only quotation and because it leads nowhere. The whole topic (even professional publishers are sometimes confused) does not really help the section forward. It almost reads as a simple sideswipe at the original author… and let’s face it that happened in spades at the time. 2. Your two paragraphs on copyleft left me little the wiser as they spend more time pointing out what it is not. 3. I am unclear what you are trying to achieve in the final OA vs. oa section. Apart from the fact that the actual prices you mention may have changed by the time your chapter is actually published, I do not understand the logic of the capitalisation. It might have helped – and presented a more balanced view – if you had included a good example of capitalised Open Access – otherwise, as with the quote of my first point, this looks a bit as if you are sniping and only pointing to negative examples. I’m looking forward to reading the rest…

Thanks, Chris. I’ll add positive examples.

The original post is at Go To Hellman blog, but TeleRead and No Shelf Required have asked permission to republish; this helps me get broader review.

Part 1 was published by Teleread on April 28.