Professor Paul J. Heald of the University of Illinois College of Law has just released a new study that puts Chris Meadows’s recent problems with out-of-print stories from Astounding Stories into perspective. Remember that it was Heald whose previous research found that extension of copyright terms actually reduced the availability of books. And his new report, “The Demand for Out-of-Print Works and Their (Un)Availability in Alternative Markets,” has found that, while demand for out-of-print books as ebooks or in other forms remains high, supply remains atrocious in comparison to older musical works.

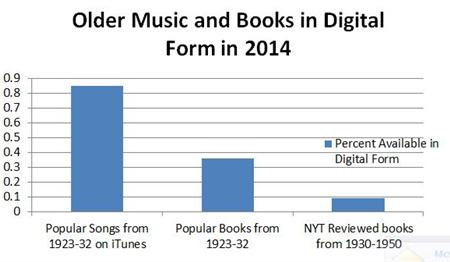

Heald compares the availability of popular songs and music from the 1920s and 1930s to the availability of popular book titles from the same periods as ebooks, demolishing the idea that there is no interest in such works. “Availability spikes for pre-1923 works, suggesting that some pent-up demand exists for older works, at least when cheap and efficient print-on-demand publishers can offer them without having to negotiate for the right to copy.” But the supply situation is a different story. As the graphic here illustrates, supply of early 20th-century popular songs on iTunes runs at around 85 percent. The figure for popular books published between 1923 and 1932 is closer to 35 percent. And for “a sample of 950 fiction and non-fiction books reviewed in the New York Times Book Review,” for the period 1930-50 it’s down to less than 10 percent.

Heald finds a stark comparison between books published prior to 1922 and released into the public domain, and those from subsequent years. “In 2014, 94% of 165 public domain bestsellers from 1913-22 were available in eBook format, up from 48% in 2006,” he states. “Data on the eBook availability of copyrighted bestsellers from the same era tells a different story. Of 167 bestsellers from 1923-32 still under copyright, only 27% (45/167) had been made available as eBooks by 2014.”

Heald concludes as follows:

“Whatever the reasons for differences in the book and music publishing industries, the lack of availability of books from the post-1923 portion of the 20th century is startling. Senator Orrin Hatch argued in defense of the 1998 term extension that maintaining the availability and distribution of works is at the heart of the meaning of “progress” in the Copyright Clause of the Constitution. He was absolutely correct about the purpose of copyright, but utterly wrong about how to solve the problem of missing works. Copyright term extensions have clearly prevented the development of a market for re-printing the massive number of “missing” works from the 20th century. If availability matters, then further attempts to extend the copyright term should be resisted, not encouraged. Copyright was not designed by the framers of the Constitution as a means by which Congress could make books disappear.”

Yes, the lagging situation for reprints of unavailable titles as ebooks is ridiculous. Yes, further copyright extensions will only make it worse. Sounds like both an opportunity – and a massive threat.

“…at least when cheap and efficient print-on-demand publishers can offer them without having to negotiate for the right to copy.”

And this is my problem with this whole concern. publishers want to be able to profit off someone else’s work with out having to pay the creator or his heirs or assigns anything. So why should I, as a published author, give a hoot abt the woes of publishers who want to rip off the creator or their heirs/assigns?

And as far as things be poorly available — interlibrary loans

“…at least when cheap and efficient print-on-demand publishers can offer them without having to negotiate for the right to copy.”

As a published author why should I care abt the woe’s of publishers that just want to rip-off the creator, their heirs and assigns?

It’s also, however, much easier and faster to turn an old recording into an MP3 than it is to turn an old print copy of a book into a good-quality epub. (Yes, with the right equipment a PDF’s very fast to make and will do just fine for print-on-demand, but many of the retail vendors don’t sell PDF ebooks.)

I’ve published, in enhanced form, a number of popular pre-1923 books and the reason is obvious. Since they’re in the public domain, there’s none of the hassle and expense of tracking down whoever owns the current copyright and paying for or getting permission. I could concentrate on making it the best possible book, often adding additional material from the same author.

And keep in mine that finding out who owns the rights to a post-1922 book can be quite difficult. Authors as prominent as John Steinbeck didn’t probate their literary estate. (His fell into the residuals going to his last wife.) Finding people, finding wills, finding heirs, getting permission can be quite costly and take years. Better to not just bother.

And it’s no secret that we got that copyright extension simply because Disney wanted to protect Mickey Mouse and bought off key members of Congress. It’s also obvious that Congress hasn’t revised copyright in any substantial fashion since the late 1970s because if it started down that path, it’d be so besieged by competing money interests that it wouldn’t know whose money to take.

People have been working on getting older music digitized for Compact Discs since the 1980s (CDs came out in North America and Europe in 1983). Then digital music (MP3s and other formats) became popular and that’s been happening for the last 15+ years (Oct. 2001 since the iPod came out and it was not the first). People were digitizing music and duplicating CDs before portable digital players (the first in 1997, I think).

I don’t want to argue specific years on when technology was “popular”, but digital music (CDs and digital players) have been popular in culture for significantly longer than eBooks. The first Kindle came out in 2007 (Sony in 2006) and it still wasn’t mainstream then.

Even if you weren’t willing to say digital music wasn’t “popular” until 1993 (10 years after it’s introduction but still 21 years ago) and eBooks weren’t “popular” until 2009 (a stretch if you ask me) that’s 4 times longer digital music has been around (if you say 2011 for popularity of eBooks then that’s 7 times longer). No matter how you want to trim those numbers digital music has been popular much longer than digital books.

It’s also significantly easier to make a decent digital recording of older music than it is to make a decent eBook (I don’t mean PDF, I mean a nice digital eBook). The music is already in a electronic analog format just waiting to be converted to digital.

Audio:

Give me a 30 minute recording with a playback device that has RCA output(s) and I can turn it into an audio file in 30 minutes. Give me another 10 minutes and I can break it up into separate files for each track. It’s going to sound decent, not professional but decent.

Books:

You’ve got to scan every page of a book (hundreds of pages) convert it to text via OCR, correct all the scanning mistakes, format it nicely (removing page numbers and headers and footers) and create a table of contents. This is a LOT of work. If the book has illustrations, it’s even harder.

For old music, many people (not all) are going to be forgiving about some crackles/pops/dropouts, it’s old music, right? An old book with formatting and spelling problems is going to be frowned upon much more, if they got it right 80-90 years ago, why can’t we get it correct now? And if it was misspelled in the original, should it be corrected now? (The note misplayed in the original music is still misplayed in the newer copy).

For books, even skipping the OCR process, just making it a PDF of scans and making an index page is still pretty time consuming and requires more effort, compared to music, and the smaller slower eBook readers are not going to give the experience the readers are used to. I don’t think this is what most people are thinking when they’re talking about older books getting converted to eBooks.

Yes, the process for all of these have changed significantly if you wanted to mass produce a digitization system for both. I’m specifically breaking it down into ultra-simplistic terms. I think that CDs and digital music players having been mainstream much much longer than eBooks is much more relevant that the process.

On the other hand, Project Gutenberg started in 1971…

(Venturing outside the copyright portion of this topic: Older music contracts have had more time to be updated with digital clauses than books.)

I might argue some different reasons for his findings. I think it is an error to assume that a large percentage of pre-1923 books are around because of a “pent-up demand” for them. I think it is more a matter of availability.

As a Project Gutenberg volunteer, I can tell you that it has become second nature any time I see a pre-1923 book to wonder if it is in the PG collection, and want to snap it up for that purpose. Over time, many volunteers doing the same means that a large percentage of English-language books from the early 20th century have been digitized, and added to that collection. This is based not on demand, but on the books (physical or page scans from another source) simply being available.

Another piece of the puzzle is that, due to PG’s place as a well-known public domain resource, and open inviting of copying of the texts, PG books are very widely copied and reused in many ways. In my experience nearly any collection of “Free, classic e-books”, (that are not page scans) originates from that source. And that applies to ebooks for sale too. There have been a number of companies that take PG texts, and repackage them as low-price e-books for sale. Again, the selection process here, from what I’ve seen, is not about carefully picking out what might be the most in demand, but taking large numbers of texts, automatically reformatting them, and being happy with whatever sales they get.