This is a follow-up to my earlier review of Rebecca West‘s immense travel book about the former Yugoslavia, “Black Lamb and Grey Falcon,” which I left out for space reasons.

The book is notoriously long, and as it happens, Rebecca West also included a lengthy aside on book size and portability that stands as a good reminder of what e-books and tablets have saved us from.

The setting is Split, on Croatia’s Dalmatian coast, which “is Diocletian’s palace: the palace he built himself in 305, when, after twenty years of imperial office, he abdicated. The town has spread beyond the palace walls, but the core of it still lies within the four gates.”

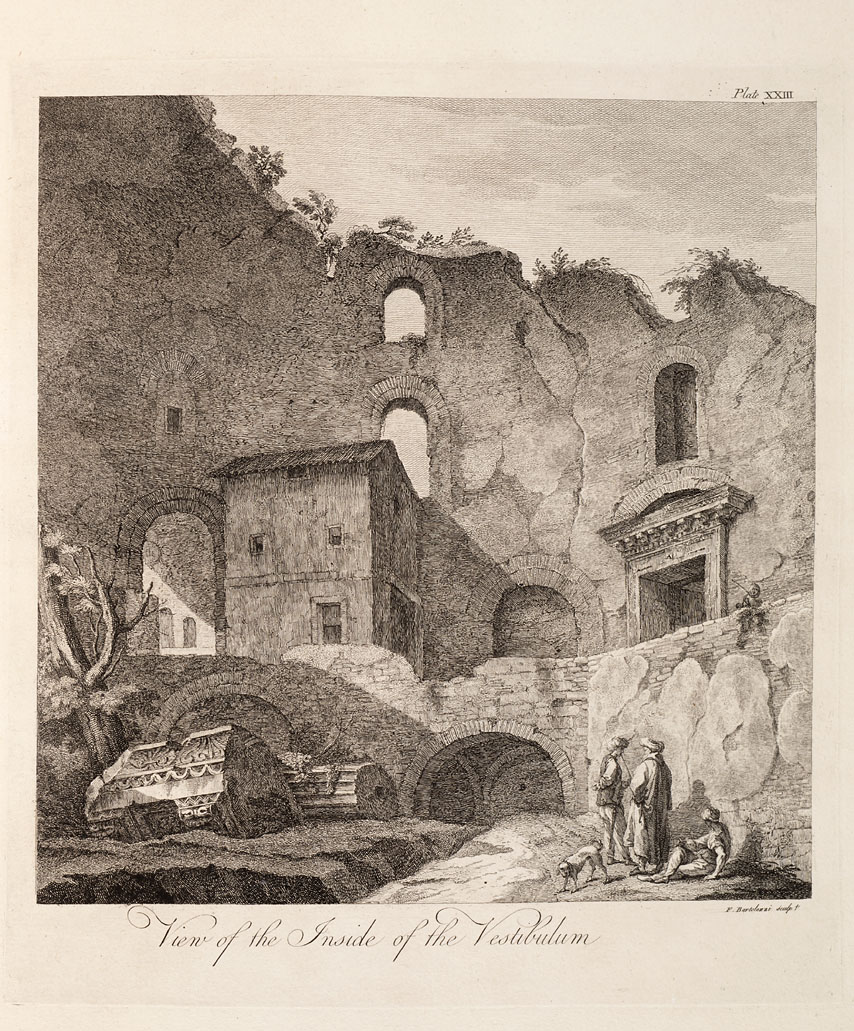

The great Scottish Neoclassical architect Robert Adam visited Split in 1757 and, under suspicion from the town’s Venetian overlords who suspected him of spying, produced a suite of sketches of the palace ruins which, when published, were very influential in the spread of the Neoclassical style, producing “the best of Georgian architecture,” in West’s words.

Adam’s “Ruins of the Palace of Emperor Diocletian at Spalatro in Dalmatia,” published in 1764, and now available free as an e-book from Archive.org, became famous for its superb engravings as much as its subject.

“I greatly wish we could have brought Robert Adam’s book of engravings with us,” says Rebecca West’s husband, upon their arrival in Split. West replies: “It is disgusting that one cannot remember pictures and drawings exactly. It would have been wonderful to have the book by us and see exactly how the palace struck a man of two centuries ago, and how it strikes us, who owe our eye for architecture largely to that man.”

“Then why did we not bring the book?” asked my husband.

“Well, it weighs just over a stone,” I said; “I weighed it once on the bathroom scales.”

“Why did you do that?”

“Because it occurred to me one day that I knew the weight of nothing except myself and joints of meat,” I said, “and I just picked that up to give me an idea of something else.”

Her husband continues: “Why didn’t we bring it, even if it does weigh a little over a stone? We have a little money to spare for its transport. It would have given us pleasure. Why didn’t we do it?”

Her husband continues: “Why didn’t we bring it, even if it does weigh a little over a stone? We have a little money to spare for its transport. It would have given us pleasure. Why didn’t we do it?”

“Well, it would have been no use,” I said; “we couldn’t have carried anything so heavy as that about the streets.”

Yes, we could,” said my husband; “we could have hired a wheelbarrow and pushed it about from point to point.”

“But people would have thought we were mad!” I exclaimed.

And Philip Thompson, a local teacher of English, observes: “They’d think it very odd here, if you went about the streets trundling a book in a wheelbarrow and stopping to look at the pictures in it – very odd indeed.”

For better or worse, you’re unlikely to hear such conversations in the tablet era. And there is one more unexpected fringe benefit of the e-book revolution: Saving the English from embarrassment abroad. Oh, and saving wear and tear on Croatian wheelbarrows.

Would reference to the tablet version have inspired the best of Georgian architecture?